Early one evening, I answered the phone.

“Hello, Mom? I just want to tell you I’m at the Krsna

temple in Potomac, Maryland. I live here now.”

by Diane Sautter

It was the rootless summer after the years of high school for my oldest son Andy. At that time he lived more or less from day today, with few plans for the future. He had his tight circle of friends, most of whom were as uncertain about life as he (although all managed a defensive bravado). Andy seemed to me to be adrift in a world without values or purpose. The family he had grown up in had broken apart through divorce at the end of his freshman year, and although as a single parent I had found my own world purposeful and personally growing, there seemed to be no way to share my reality with Andy. The strangled communication from our former family life had carried over and left him in particular (I have two other, younger sons also) in an isolated adolescent vacuum. Love occasionally struggled its way across the chasm between us, painfully, but I seemed unable to alleviate his suffering. He had found nothing of value in high school, and his abilities in art and music were used less and less, from lack of motivation.

It was the rootless summer after the years of high school for my oldest son Andy. At that time he lived more or less from day today, with few plans for the future. He had his tight circle of friends, most of whom were as uncertain about life as he (although all managed a defensive bravado). Andy seemed to me to be adrift in a world without values or purpose. The family he had grown up in had broken apart through divorce at the end of his freshman year, and although as a single parent I had found my own world purposeful and personally growing, there seemed to be no way to share my reality with Andy. The strangled communication from our former family life had carried over and left him in particular (I have two other, younger sons also) in an isolated adolescent vacuum. Love occasionally struggled its way across the chasm between us, painfully, but I seemed unable to alleviate his suffering. He had found nothing of value in high school, and his abilities in art and music were used less and less, from lack of motivation.

Into this gap after high school came the idea of a junket with two or three of his friends. All I knew of their journey was that they planned to stop at a Krsna temple for a “big feast”—something one of his friends had experienced before.

I didn’t hear from Andy for two or three weeks after they left. Then, early one evening, I answered the phone and was relieved to hear his voice, sounding clear and positive.

“Hello, Mom? I just want to tell you where I am. I’m at the Krsna temple in Potomac, Maryland.”

“You’re still there?” I queried.

“Yeah. Well, I decided to stay. I live here now.”

“You live there?”

“Yeah. We’re all devotees here.”

I paused, reflecting on the strange word “devotee” and the calmly serious sound of Andy’s voice. I didn’t know exactly what a “devotee” was, yet something in his tone made me feel optimistic. I asked, “Are you still with your friends?”

“No. They left. They—well, you know those two—they couldn’t hack the disciplines.”

So his friends had departed to wander and Andy had stayed!

“What do you do there, Andy?”

“Well, I’m working on a little barn for the bull. We have a young bull calf here; he’s sort of a pet. You know—we don’t eat meat, or use any intoxicants, have any illicit sex, or do gambling. Everything we do is to serve Krsna.”

This was a lot for my son to say. He was groping to tell me about his life there, but the life was very new to him and a great change from his habitual Western adolescent behavior. I wanted to help him explain more.

“How do you understand Krsna, Andy? Is this a religion? Tell me about it.“

He hesitated, and I heard him turn to someone else nearby and ask, “Hey, Bhakta Joe, my mother wants to know who Krsna is.” There was a sound of voices talking informally, and then Andy returned to the phone.

“Krsna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord of the universe. That’s all we do here. We serve Krsna.”

There was more to this conversation—for instance, did he need anything’? However, for the first time in years, I heard in Andy’s voice something I had been aching to hear: a sense of direction, a sense of connection to something he valued. I wasn’t listening to his words as much as I was listening to a tone of voice that said life was finally worthwhile. My mind trotted out the usual questions: Why call God Krsna? What was the group life really like there? Why had he stayed when his restless friends, who were older and whom he tended to emulate, had left? What had he found that was helping him change his life? The questions went unanswered at this time, yet I felt good at the end of our conversation when he asked me to come down to visit him there: we were “in touch:” Whoever this Krsna was, I apparently already owed Him a debt of gratitude.

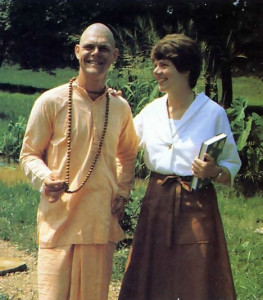

This gratitude and spirit of inquiry became the basis for my interactions with Andy and with other devotees at the temple. A few months later, I arrived for my first visit at the camp in Potomac which had been turned to new use as a home for the Washington branch of ISKCON. Andy looked amazing: the shaven head and little tuft of hair at the back surprised me. When he was a baby it had taken about eight months for his hair to come in—now, with his Krsna haircut, he reminded me of his original newborn state. He had the look of a person beginning life all over again. More than this, his eyes were clear and direct, and his approach to me warm. Gone were the hostility and shiftiness of communication which had plagued our relationship. He had been signing his letters to me “Your humble servant”—a phrase adopted from the spiritual preceptor of the Krsna movement, Swami Prabhupada. And now I could see it was more than a parroted phrase. It seems that by discovering God as his friend, and himself as a friend to God, Andy had also found his own capacity to be a friend to all other living beings, even to his mother.

My time at the temple was gratifying. The other devotees were courteous and helpful, and I was eager to hear from them about their lives there. I attended the early morning arati, a ceremony for greeting the Deities every day at 4:30 A.M. I was not accustomed either to the early hour or to the way the devotees worshiped the Deities, but I could see that what mattered was what was in the devotees’ hearts, not what my mind conjectured about the figures on the altar. Here, obviously, was an attempt to practice loving God with all the heart, soul, and mind, in the most personal way possible, as Krsna—not as an abstract God, but as a perceived person and presence.

I have grown to appreciate the theological depths of the Krsna movement more than I ever thought I would in those early days at the temple, when I questioned the cost of the profusion of flowers on the altar. I have learned that Krsna dwells in every living being as the Supersoul and source of inner guidance. The devotee also knows that he or she is part and parcel of the Supreme Consciousness, with the qualities of God but in a much smaller quantity than God. God is the complete whole, whereas each one of us is merely a fragmental part. The joy of the Krsna devotee seems due to the discovery that he or she is a fragmental part becoming conscious of his or her relationship to God—and Krsna consciousness, devotional service to the Lord, is the process for going back, as they say, to Godhead. The devotee celebrates this relationship with God and makes it real in his own life through singing the Lord’s name and dancing. This is bhakti-yoga—the yoga of love.

Perhaps it is this chanting and dancing which has led parents and others aware of the Krsna movement to make accusations about “cult” behavior. Yet the same people don’t bat an eyelash when their sons and daughters go to discos to dance and celebrate sex and intoxication. By contrast, the thirty or forty devotees at the Potomac temple are actively working to purify their lives by following a code not unlike the Ten Commandments. Drumming, playing hand cymbals, leaping, and chanting Krsna’s name with great gusto, they dance and sing to celebrate God’s presence in their lives and to open up more completely to that presence. The world doesn’t mind when people celebrate sex and intoxication, but everyone becomes extremely concerned when young people begin to wholeheartedly celebrate God. Love of God has probably always been socially and culturally threatening—we see that in the life of Christ.

Of course, the real question for me, and for every parent, is how to behave when we are confronted with something strange and new which at first we may not understand. Perhaps because I work as a counselor, a trained listener, my natural approach was Tell me about it. From the beginning of my son’s affiliation with Krsna consciousness, I have been feeling my way along, learning a religious system to a large extent new to me, although one of the oldest in the world. I have studied all sorts of graduate-level textbooks on religion, and yet the many volumes of the Srimad-Bhagavatam, translated and explained by the scholarly Swami Prabhupada, remain the most complete and articulate I have ever encountered.

When I see my son now, I see a young man growing into his prime, with a security and breadth of development rare in Western culture. Perhaps because the whole science of the soul is encompassed in the Bhagavatam and because the main scripture of the Hare Krsna movement, the Bhagavad-gita, is so theologically profound, Andy—now Apauruseya, by initiation—knows who he is and how he is related to God and the universe. He has superb ways to grow, with appealing models in the Bhagavatam and the high standard set by his spiritual master. He has a strong desire to serve Lord Krsna and a practical, down-to-earth way of fulfilling that desire. He’s reaching out to people by introducing them to the ancient books on self-realization.

At my last visit with my son—the latest in a line of nine or ten increasingly cordial and happy times I have spent with him in the past three years he has lived at the temple—we sat talking for an hour in the bus station, waiting for my Greyhound to carry me back to the usual Western routines. People looked at us. Apauruseya was in his pale orange robes—he had just come from leading that evening’s chanting at the temple. I felt his calmness and conviction radiating and was proud of his dedication. There in the bus station filled with bored and idle people, we alone seemed to be experiencing a real person-to-person relationship. This was possible not only because I respect his choices, but because his choices are right choices for him; they are commitments based on a deep understanding of human life and its divine purpose. The Krsna devotee is indeed a friend to all—even his mother feels served with an open heart.

Leave a Reply