After fifty centuries,

the encounter between Lord Krsna and

His hundred-headed adversary is still celebrated.

by Drutakarma dasa

Last summer I went to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to see “The Sensuous Immortals,” a sculpture exhibit from the Pan Asian Collection. Among the pieces were many Visnu and Krsna Deities. Some came from Angkor Wat, the great ruined temple complex in Cambodia. Others were from as far away as Indonesia. At one time, the archaeological record shows, the culture extended. in a huge arc: from Java to Indochina, throughout India (of course), and west to the Iranian border.

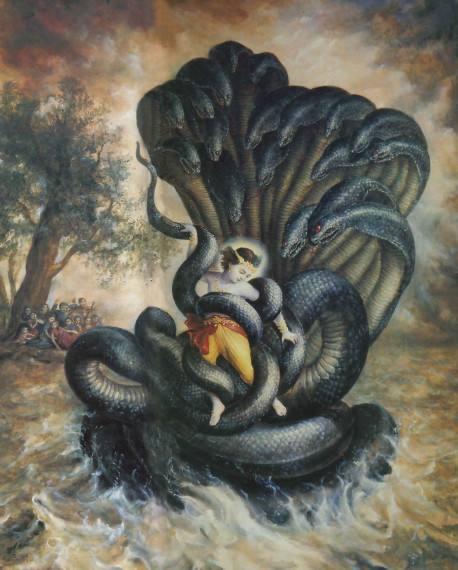

A little girl was surveying a bronze figure—Krsna playing His flute and dancing on the head of a huge serpent.

“Is that God ?” she inquired of her well-attired mother.

Perhaps remembering a college art history course, the lady said, “Yes, dear, that’s God.”

“What’s His name?” the girl persisted.

Casting a glance at the identifying card, she said, “Krsna. Its a form of Krsna.”

“Why is He dancing on the snake’s head?”

“It doesn’t say.”

“The Sensuous Immortals.” I liked the title. (Of course, Lord Krsna isn’t sensuous, but He is sentient.) Many people believe that after death we all merge into the Supreme and lose our individuality and sensation. A more careful reading of the Vedas, however, reveals that the individual self is immortal and after “death” acts through spiritual senses. And among all the immortals, one is supreme. Krsna, the Supreme Lord, pervades the entire universe and simultaneously exists in a humanlike form with transcendental senses.

Periodically, Krsna descends to earth to display His lila, or pastimes, and invites us to take part in them. Somehow, we have come to this less-than-ideal world to enact our own “pastimes” (getting old, getting sick, dying and taking new bodies, sometimes even animal bodies). But by meditating on Krsna’s pastimes, we prepare ourselves for reentering them.

Fifty centuries ago, Lord Krsna made His appearance in Mathura, a district about ninety miles south of New Delhi, on the way to Agra (the site of the Taj Mahal). The Greek geographer Ptolemy called it Modoura, the city of the gods. The historian Arrian referred to it as Methoras, the capital of the Souraseni, the descendants of King Surasena (Krsna’s grandfather). As soon as Krsna appeared there, however, His father Vasudeva carried Him across the river Yamuna to Vrndavana to save Him from King Kamsa, who wanted to kill Him.

In his Ancient Geography of India (1871), a British major general named Alexander Cunningham relates, “Vrndavana means the ‘grove of basil [tulasi] trees,’ but the earlier name of the place was Kaliyavarta, or Kaliya’s whirlpool, because the serpent Kaliya was fabled to have been taken up his abode just above the town . . . [near] . . . a kadamba tree overhanging the Jumna. Here he was attacked by Krsna.” The spot is still there. This past spring I happened to visit it while on pilgrimage.

Things haven’t changed so very much since the time Krsna played in Vrndavana as a cowherd boy. On the outskirts, in Ramana Reti, peacocks still dance beneath the trees. If you’re not careful, monkeys will steal fruit from your room. Cowherd boys lead white cows along dusty paths to graze for the afternoon in the shade of tall trees. Everywhere you can hear songbirds. And beyond the wheat fields, flower gardens, and orchards, the river Yamuna shimmers invitingly.

Ptolemy knew this river as Diamouna; Pliny’s Latin name for her was Jomanes. Over the centuries the course of the Yamuna has shifted somewhat. Now the old riverbed is part of a pilgrimage path that encircles Vrndavana village. Along the path you walk past many small temples that mark the places of Krsna’s adventures. One cool evening late in March, before the onset of the hot season, I was walking the path with other Western devotees, passing village women who balanced brass water jugs on their heads, old farmers who drove bullock carts, and Indian pilgrims who greeted us with Krsna’s names.

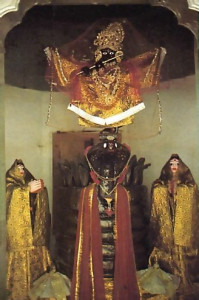

With the sun just setting, we came upon the place called Kaliya-ghata. In the shade of ancient trees stood a modest stone temple. As we peered into a small shrine, we could see the Krsna Deity playing His flute and dancing on the hoods of a many-headed serpent. The Deity was not at all unlike the one in Los Angeles, except that here the temple priests were performing age-old rites of worship. Patita-pavana dasa, an American devotee who had lived on the subcontinent for several years, began recounting the battle between Lord Krsna and the great serpent Kaliya.

While tending the cows, Krsna and His friends sometimes came to the bank of the Yamuna. One summer’s day the boys and cows felt exceptionally thirsty and started drinking the water. But the river was tainted with Kaliya’s venom, and the boys and cows fell to the ground, apparently dead. The venomous vapors had even dried up the nearby trees and grasses, and when birds flew overhead they fell into the water and died. But Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, restored everyone and everything to life by His mere glance. I couldn’t help thinking that environmentalists would appreciate this. The Supreme fights water pollution.

In any case, now Krsna turned His gaze on Kaliya. First Krsna climbed up into a huge, yellow-flowered kadamba tree (the one mentioned by Major General Cunningham). Then He jumped out of the tree and into the water. Kaliya surfaced and angrily grabbed Krsna in his coils. Seeing their beloved friend in such danger, the cowherd boys became overwhelmed with anxiety. They wanted to help Krsna, but they could only stand on the bank and cry.

Meanwhile, the earth trembled and meteors fell from the sky. Looking on from a distance, Krsna’s foster father Nanda Maharaja and the other cowherd men of Vrndavana were horrified. “Krsna is in danger!”

Ordinarily, we think of God as our all-provident father and approach Him in a mood of supplication. But the residents of Vrndavana saw Krsna as their friend and child and so approached Him with unalloyed devotion. This is life’s highest attainment—pure love of God.

All the residents of Vrndavana—men, women, children, and even animals—rushed to the bank of the Yamuna to see Krsna. But Krsna’s older brother Balarama simply stood there smiling. He knew that Krsna was supremely powerful and that He could easily defeat the serpent. Balarama could tell that Krsna was just allowing the residents of Vrndavana to increase their love for Him. (In the Vedic tradition, God is seen as the central object of love, because all other love—for friends, family, or country—is temporary.)

When Krsna’s mother Yasoda arrived, she wanted to jump into the river, but her friends stopped her. So she stood and watched, transfixed with grief for her beloved child. (Of course, in the strict sense the Lord has no mother, but He allows a devotee who loves Him with motherly affection to act in that capacity. In much the same way, one can approach Krsna in the mood of friendship or conjugal love.)

For two hours Krsna remained in the grip of Kaliya’s coils. But when all the inhabitants of Vrndavana were practically at the point of death out of affection for Him, Krsna broke free. Then He jumped atop the serpent’s hoods and danced on them. Kaliya tried to knock Krsna down with the rest of his hoods (he had a hundred), but Krsna eluded them all, Krsna danced with sublime aesthetic grace, all the while striking Kaliya harder and harder. Soon the enraged serpent spewed poison and fire. He was struggling for his very life.

When Kaliya raised a hood in one last attempt to kill Krsna, Krsna kicked it down. Finally Kaliya began to realize who Krsna was, and the serpent’s wives begged Him to spare their husband’s life. The Lord agreed, but ordered Kaliya to leave the Yamuna for the ocean. (Based on geographical descriptions in the Vedas, it is sometimes said that he went to Fiji, where to this day the natives tell of a black serpent inhabiting a lake in the mountainous interior.)

Sitting underneath the kadamba tree at Kaliya-ghata at twilight, I meditated on this pastime, as cows wandered over the spot where it had taken place. That’s what’s so attractive about Vrndavana—it’s easy to think of Krsna. As the authors of the British Imperial Gazetteer noted in the nineteenth century, “The western side of the district [of Mathura] is celebrated as Braj Mandala [Vrndavana] or the country of Krsna, and almost every grove, mound, and tank is associated with some episode in His life.”

Suddenly I remembered the little girl in Los Angeles asking, “Why is Krsna dancing on the snake’s head?” This article is, in a sense, an answer to the question her mother couldn’t answer.

Leave a Reply