The various meanings of dharma reveal

a richness of concept and a unique experience.

by Garuda dasa

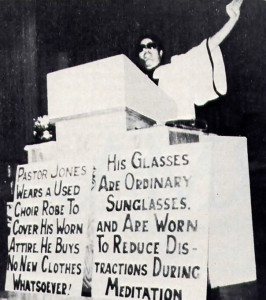

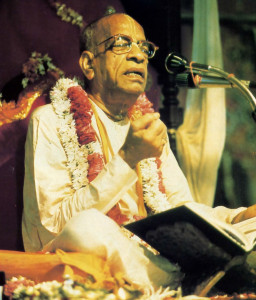

The concept of dharma is of central importance in Vaisnava (Krsna conscious) philosophy and practice. So important is the concept that His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada actually defines the central teaching of Vaisnava philosophy, bhakti, in terms of dharma. Therefore, if one desires to understand bhakti, an understanding of dharma is essential. The purpose of this study is to examine the dimensions of dharma that contribute to an understanding of the genuine experience of bhakti.

The concept of dharma is difficult for the Westerner to understand. Many a student and scholar of Indian religion and philosophy has failed to arrive at a full sense of its meaning and has put forward incomplete and faulty interpretations, thus demonstrating dharma’s seeming foreignness. Because the West has no experience that is the equivalent of dharma, we have neither a direct nor adequate English translation of the word. To account for the complexity of this concept, and for the difficulty Westerners have in understanding it, I will analyze the various dimensions of dharma as they are exhibited in the extensive writings and translations of Srila Prabhupada.

The Problem of Translation

The various specific meanings of dharma, which emerge through the context in which the word is found, reveal the richness of the concept and will gradually introduce us to a unique experience. In his writings, Srila Prabhupada often translates dharma simply as “religion.” But he indicates that he uses this particular translation for convenience and for want of a better single English term, and he expresses dissatisfaction with a translation that could be misleading. In the introduction to his translation of the Bhagavad-gita, Srila Prabhupada notes that the word religion “conveys the idea of faith, and faith may change.” If a person’s religion can change, then it is not eternal but temporary, and therefore material. Thus in his introduction to the Gita, he cautions the reader that dharma translated as “religion” is intended to mean truly spiritual religion, which is eternal, changeless.

At the same time, as Srila Prabhupada also mentions, the word dharma does appear sometimes in the traditional Hindu context of the four purusarthas, or standard, mundane aims of life: dharma (religiosity), artha (economic development), kama (sense gratification), and moksa (liberation). Here Srila Prabhupada translates dharma as “mundane religion.” He rejects this sense of dharma for the same reason that he objects to the sense of religion as “changeable faith.” In his commentary he explains that dharma here means simply the pursuit of materialistic interests. The God explains that this dharma is embraced is phalakanksi, desirous of the fruits of his labor, or by a rajasi; a passionate person. Dharma in the specific context of the purusarthas is always temporary and mundane, and so Srila Prabhupada always distinguishes between dharma in this context and dharma in its other contexts. Religion interpreted as mere “religious faith” is practically the same as dharma in the mundane purusarthas context, and therefore he is careful to distinguish between ordinary religion and genuine dharma.

We may also understand dharma by examining religion that is considered not dharma. Srila Prabhupada describes this kind of irreligion as kaitava-dharma, which he translates as “religious activities that are materially motivated. Srimad-Bhagavatam further qualifies kaitava-dharma as five kinds of irreligion, or vidharma. Vidharma refers not just to the materialistic “religion” of the purusarthas, but to a complete misuse or distortion of religion.

Less ambiguous than the translation “religion” is the translation “religious principles” or “the principles of religion.” Srila Prabhupada uses this translation of dharma more frequently. This slightly expanded translation conveys the sense of religion that is unchanging, that is intrinsic to human existence. However, even this translation of dharma does not fully reveal the complexity and depth that dharma has in the writings of Srila Prabhupada. Although he uses convenient English terms for the purposes of translation, and although the context in which dharma is found does surely contribute to its sense, he does not rely on these simple translations to convey the full meaning that dharma has in Vaisnava philosophy. The struggle in translation merely gives us a clue as to dharma’s profundity. Now let us examine the various ways in which dharma functions philosophically in the thought of Srila Prabhupada.

The Ontological Foundation of Dharma

An analysis of dharma in terms of its ontological, sociological, and theological dimensions is justified, because the word takes on many prefixes that indicate these levels of meaning. These prefixed meanings also are often implied by the context within which the word dharma alone is found. However, we will find that the ontological analysis demonstrates a common denominator in all these meanings of dharma, providing an underlying meaning upon which other meanings are built. The ontological, sociological, and theological levels, on which dharma functions in intricate ways, are all collapsed into the single word dharma. Thus the complexity of the concept can be seen in the various ways in which the word is applied in Vaisnava philosophy.

Srila Prabhupada establishes the ontological foundation of dharma first by referring to the word’s etymological root. * (The verbal root of dharma is dhr, which may mean “to hold,” “to bear,” “to support,” to sustain,” and so on.) He states, “dharma refers to that which is constantly existing with the particular object.” He illustrates this point with the metaphor of fire: the constituent qualities of fire are heat and light, without which fire could not exist as fire. “The warmth of fire is inseparable from fire; therefore warmth is called the dharma, or nature, of fire.” Thus the dharma of the living being is that which is inseparable from him, that which is his essential nature and eternal quality. It is that which “sustains one’s existence.” What, then, is the dharma of the living being?

As Srila Prabhupada explains, the very dharma (or essential characteristic and occupation) of the living being is service. “Service” presupposes action, and the Bhagavad-gita states that it is impossible for the living being to cease from action even for a moment. Commenting on this verse, Srila Prabhupada says that “it is the nature of the soul to be always active.” Furthermore, he observes that all actions performed by living beings are ultimately service, and that “every living creature is engaging in the service of something else.” So characteristic is the quality of service that it is seen to be the innate tendency of all living beings, an “essential part of living energy.” Thus “service” is presented as an irreducible quality of life.

It is “service” itself which is the sanatana-dharma, or “eternal” religion, of the living entity. In the Sri Caitanya-caritamrta, to, Lord Caitanya states that the svarupa, or constitutional position, of the living being is the rendering of service to God. From this statement, Srila Prabhupada deduces that there is no living being who does not render service, and that at no time does the living being stop rendering service.

If we analyze this statement of Lord Caitanya’s, we can easily see that every living being is constantly engaged in rendering service to another living being. . . . A serves B master, B serves C master, C serves D master, and so on . . . In this way we can see that no living being is exempt from rendering service to other living beings, and therefore we can safely conclude that service is the constant companion of the living being and that the rendering of service is the eternal religion of the living being.

The living being’s dharma of service is not just in relation to other living beings, but is related ultimately to God, or the complete whole. Dharma as service refers to that metaphysical position of the living beings as very small parts in relation to God, or the complete whole. If the living being does not consciously participate in, with knowledge of, the complete whole, then his life becomes incomplete:

. . . living beings are parts and parcels of the complete whole, and if they are severed from the complete whole, the illusory representation of completeness cannot fully satisfy them.

The completeness of human life can be realized only when one engages in the service of the complete whole. All services in this world—whether social, political, communal, international. or even interplanetary—will remain incomplete until they are dovetailed with the complete whole. When everything is dovetailed with the complete whole, the attached parts and parcels also become complete in themselves.

The incompleteness experienced by living beings indicates that they strive for completeness, and this is achieved through a “dovetailing” of service with the complete whole. The living entity’s full and conscious participation in activities that harmoniously serve the whole is service.

The Sociological Dimensions of Dharma

The Hierarchical Organization of Human Service

The different types of actions that humans perform are dovetailed led with the complete whole through the function of dharma in the socio-ethical system called varnasrama–dharma. This system gradually elevates human beings to conscious participation in the complete whole. Here dharma encompasses the full range of human duties and actions in the world in relation to the elevation of the soul to perfection.

Dharma, or “occupational duty,” as Srila Prabhupada most often translates it in the context of varnasrama, is the organization of the various types of human service for the ultimate aim of perfecting that service characteristic. The principle is that a person attains perfection by performing his proper work. He accomplishes this first by identifying the particular nature of his own service, or sva–dharma, according to his particular psychophysical condition and harmoniously accommodating it into the total scheme of a God-centered society.

Service is qualified according to progressive stages of life and principal categories of work. The four stages of life, or asramas, consist of a student stage, a working stage in married life, a stage of withdrawal from both work and household life, and a last stage of complete renunciation. The varnas, which come into play in the second stage of asrama (the household stage), are four basic classes or categories of practical work: the teaching class, the administrative and martial class, the professional class, and the working class, which serves the first three classes. The varna and asrama of a particular person are determined by that person’s qualities, or guna, and by the nature of his past and present activities, or karma.

The varnasrama–dharma is an arrangement of classes of human service according to people’s various qualities and activities which directly reflect various degrees or levels of awareness of the complete whole. Srila Prabhupada explains that “a living being is meant for service activities, and his desires are centered on such a service attitude. . . . The perfection of such a service attitude is attained only by transferring the desire of service from matter to spirit . . .” As our service becomes gradually directed away from matter toward pure spirit and our desires become completely purified, we progress to higher occupational duties. The different occupational duties indicated by the varnas correspond to different stages of our evolving consciousness of the complete whole. For example, the development of consciousness of the public administrator is greater than that of the professional, and the latter’s development of consciousness is greater than that of the simple laborer. The teaching class, or brahmana class, have the most developed consciousness, because to teach they have to realize the complete whole, or Brahman.

The varnasrama–dharma system presupposes the realities of karma and the transmigration of the soul; a person can improve his human status of activities by performing his proper occupational duties in this life, thereby qualifying himself for higher or more advanced activities in the next human birth. “The system of the sanatana-dharma institution is so made that the follower is trained for the better next life without any chance that the human life will be spoiled.”

Universal Characteristics of Society

It is important to note that in the above quotation varnasrama-dharma is called the “sanatana-dharma institution.” This expresses still another philosophical understanding about varnasrama-dharma. Here Srila Prabhupada indicates the eternal function of the varnasrama sociological principle, describing the very dharma of human society itself:

No one can stop the system of varna and asrama, or the castes and divisions. For example, whether or not one accepts the name brahmana, there is a class in society which is known as the intelligent class and which is interested in spiritual understanding and philosophy. Similarly, there is a class of men who are interested in administration and in ruling others. In the Vedic system these martially spirited men are called ksatriyas. Similarly, everywhere there is a class of men who are interested in economic development, business, industry, and making money; they are called vaisyas. And there is another class who are neither intelligent nor martially spirited nor endowed with the capacity for economic development but who simply can serve others. They are called sudras, or the laborer class. This system is sanatana—it comes from time immemorial, and it will continue in the same way. There is no power in the world which can stop it.

Because varnasrama-dharma was created by God, it can never be destroyed, although it may be distorted or perverted, as in the present-day caste system.

Varnasrama-dharma is carefully distinguished from the present caste system found in India, where a person’s varna and asrama are decided solely by his birth. At present, even if a person born into a family of laborers acquires the qualities of a learned brahmana, still, according to the present caste system, he must remain a laborer. But Srila Prabhupada states that a person’s varnasrama-dharma must be determined by his present qualities and that such an intelligent person should take up the appropriate varna despite a familial orientation toward a different varna. This principle is confirmed in the Srimad-Bhagavatam.

The Paradoxical Nature of “Varnasrama-dharma”

Although Srila Prabhupada advocates the varnasrama-dharma system as a means of gradual spiritual advancement, he states that in the present age the perfect practice of varnasrama-dharma cannot take place:

The purpose of work is to please Visnu. Unfortunately people have forgotten this. Varnasrama-dharma, the Vedic system of society, is therefore very important in that it is meant to give human beings a chance to perfect their lives by pleasing Krsna. Unfortunately, the varnasrama-dharma system has been lost in this age. . . . Although we may try to revive the perfect varnasrama system, it is not possible in this age.

Not only is the varnasrama system impractical for this age, but it is neither entirely nor ultimately necessary: “Varnasrama-dharma is the systematic institution for advancing in worship of Visnu. However, if one directly engages in the process of devotional service to the Supreme Personality of Godhead, it may not be necessary to undergo the disciplinary system of varnasrama-dharma.”

We can transcend varnasrama-dharma by attaining the goal of varnasrama-dharma, which is the full and direct service to God. However, transcending varnasrama-dharma does not necessarily entail the renunciation of the social system. We find that even when the goal of varnasrama-dharma (knowing and pleasing God) is reached, the system is still utilized, although the distinctions between services become unnecessary when all the social orders are completely absorbed in satisfying God:

Everyone’s aim should be to satisfy the Supreme Personality of Godhead by engaging his mind in thinking always of Krsna, his words in always offering prayers to the Lord or preaching about the glories of the Lord, and his body in executing the service required to satisfy the Lord. . . . In executing the prescribed duties of life, no one is higher or lower; there are such divisions as “higher” or “lower,” but since there is actually a common interest—to satisfy the Supreme Personality of Godhead—there are no distinctions between them.

The devotee of God (or, the Vaisnava) transcends all service distinctions but retains his position in varnasrama-dharma, because he is fully satisfying God in that position. Recognizing his particular psychophysical qualities and limitations, he transcends them by engaging them in service to God, thus fulfilling the spiritual purpose of varnasrama-dharma. Conversely, one who ignores his nature and qualities becomes unconsciously dominated and limited by them, causing his own future bondage in the material world.

Another aspect of transcending varnasrama-dharma is that once a person is totally purified, he can take up any varna for the service of God, whereas ordinarily, while still undergoing purification from material conditioning, a person should perform only his own duty. The examples of Parasurama and Visvamitra are given as examples of those who, though originally of one varna, at times acted in another varna.

Varnasrama-dharma is rejected in the discussion between Lord Caitanya and Ramananda Raya. Here Lord Caitanya asks about the ultimate goal of life. Ramananda Raya suggests that it is the execution of prescribed duties to awaken God consciousness, and he quotes the Visnu Purana:

“The Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Visnu, is worshiped by the proper execution of prescribed duties in the system of varna and asrama. There is no other way to satisfy the Supreme Personality of Godhead. One must be situated in the institution of the four varnas and asramas.”

Commenting on Lord Caitanya’s response to Ramananda Raya, Srila Prabhupada states, “The system of varnasrama is more or less based on moral and ethical principles. There is very little realization of the Transcendence as such, and Lord Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu rejected it as superficial and asked Ramananda Raya to go further into the matter.” It is only when Ramananda Raya suggests the giving up of all occupational duties in order to render service directly to God that Lord Caitanya is satisfied.

Although Lord Caitanya rejected varnasrama as being external, we know from the Sri Caitanya-caritamrta that He rigorously upheld the practice of recognizing the varnas and asramas in His own dealings and advocated the maintenance of etiquette between them. This paradox is also found in the Bhagavad-gita: Arjuna is told to take up his position as a warrior and fight in the battle. But at the very climax of Krsna’s instruction, Arjuna is told to abandon all varieties of dharma, or occupational duties, and to come directly to Him as the only shelter. Yet we know from the Bhagavad-gita and the Mahabharata’s account of the great war at Kuruksetra that Arjuna does in fact take up his occupation as a warrior and fight the battle. Does this mean Arjuna disregards Krsna’s paramount instruction to take complete shelter of Him? No, not at all. Arjuna’s example epitomizes the paradoxical relationship between the perfect stage of surrender both to God and to occupational duty, to the dharma of varnasrama. We know from Srila Prabhupada’s writings that the perfection of dharma as religion is complete and utter surrender to God along with complete engagement in service to Him, and that the whole purpose of varnasrama-dharma is to raise a person gradually to this perfection. But once a person attains this perfection and has given up everything (including all occupational duties) in surrender to God, only then does he have the opportunity of entering back into various positions of varnasrama for the sole purpose of pleasing and serving God. The principle is that a person must first reject occupations or dharmas for God, and then he must take up, after he has completely surrendered to God, in order to use them perfectly. Srila Prabhupada calls this “daiva”-varnasrama-dharma. Thus the varnasrama-dharma system organizes the full range of human service or activities while a person is still in a materially conditioned state, and it also may organize the various activities performed directly for God. Therefore varnasrama-dharma is never fully rejected—on the contrary, it is used both for the gradual attainment of spiritual perfection and also for assisting and expressing the direct service of God.

The Theological Dimensions of Dharma

The “Order” of God

We have discussed the ontological dimension of dharma as “service,” which Srila Prabhupada calls “sanatana-dharma.” We have also seen in varnasrama-dharma that the irreducible factor of “service” is qualified according to the natural, universal divisions of life and work, and dharma here is “occupational duty.” We saw how these qualified states of service, representing different levels of spiritual development and awareness, were organized for the aim of perfecting service, and how, once having perfected service, a person naturally performs his occupational duty to please God. This is called daiva-varnasrama-dharma, where dharma consists of one’s “divine service.” There is still another sense in which the word dharma is used, and this involves its theological dimension.

At a theological level, dharma takes on a different sense as “bhagavata”-dharma, or the dharma of God. According to Srila Prabhupada, Bhagavata-dharma offers the “simplest definition” of dharma, defining dharma as “the order of the Supreme Being.” The meaning of Bhagavata-dharma is further revealed by a key statement from the Srimad–Bhagavatam: dharmam tu saksat bhagavat-pranitam. This says that actual dharma, or religion, is directly (saksat) manifested from God. (And that is the literal meaning of bhagavata-dharma.) Thus dharma in bhagavata-dharma, as “order,” has the distinct character of sabda-brahma, or the revelation of God.

Srila Prabhupada repeatedly emphasizes the definition of dharma as “the order of God,” demonstrating what religion is and what it is not. He insists that “we cannot manufacture dharma.” He reasons that “no one can manufacture state laws; they are given by the government.” Similarly, dharma cannot be manufactured, but must be revealed by God. “In bhagavata-dharma there is no question of ‘what you believe’ and ‘ what I believe.’ Everyone must believe in the Supreme Lord and carry out His orders.” It is on the authority of God’s “order,” or revelation, that dharma is based. This kind of dharma can be transmitted only by God’s representatives.

Bhagavata-dharma is not sectarian religion; it is that universal religion which shows how everything is connected with God. Srila Prabhupada states, “Bhagavata-dharma has no contradictions. Conceptions of ‘your religion’ and ‘my religion’ are completely absent from bhagavata-dharma,” and therefore one’s identity as a “Hindu” or “Christian” or “Buddhist,” or whatever, is superficial because these identities do not necessarily mean that one is performing bhagavata-dharma, or fulfilling the order of God. However, Srila Prabhupada accepts the diversity of religions: “Since everyone has a different body and mind, different types of religions are needed.” He also explains that different religions exist because of disagreements based on these limited material conceptions and differences. But “the Absolute Truth is one, and when one is situated in the Absolute Truth, there is no disagreement.” On the spiritual platform we find no differences or disagreements, simply a “oneness in religion.”

The “order of God” is defined more specifically as the order to live according to the instruction of God. In the discussion of bhagavata-dharma as supreme religion, verse 18.66 from the Bhagavad-gita is usually presented, because therein the necessity of “surrender to God” is declared by Krsna Himself: sarva-dharman parityajya mam ekam saranam vraja—“Abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me.” Srila Prabhupada points out that the word ekam, meaning “one,” shows that religion is ultimately one. The very unity of religion is realized in bhakti, wherein one finds the full realization and perfection of dharma.

The Perfection of Service as Bhakti

Bhagavata-dharma and sanatana-dharma meet in bhakti. Bhakti means the living entity’s response to the order or message of God by consciously participating in His plan as an eternal servitor:

Factually we are related to the Supreme Lord in service. The Supreme Lord is the supreme enjoyer, and we living entities are His servitors. We are created for His enjoyment, and if we participate in that eternal enjoyment with the Supreme Personality of Godhead, we become completely happy. . . . It is not possible for the living entity to be happy without rendering transcendental loving service unto the Supreme Lord.

This participation of the living being as an eternal servitor of God is called yoga,’ it consists in the connection of the living entity to the supreme Deity. This connection, or yoga, is made possible by the revelation of God, or bhagavata-dharma, which Srila Prabhupada says “captures the presence of the Supreme,” and the living being’s response of surrender and service to God. This connection is called bhakti-yoga.

Many Western scholars, and even many Hindus, translate the word bhakti most often as “devotion,” and sometimes as “love” or “worship,” which themselves are not unacceptable but may render the word ambiguously. Too often the Westerner takes these translations and relegates the experience of bhakti either to the mere subjective and emotional or to the realm of peculiar phenomena in the history of religions. But Srila Prabhupada’s contrasting translation of bhakti as “devotional service” is truly significant, because it indicates that bhakti is not an isolated emotional experience, but rather a genuine cognitive experience in direct response to the supreme reality.

It is important to note that in the translation “devotional service,” “devotion” is not the primary element, but qualifies the substantive “service.” But bhakti is not just any service; rather, it is devotional service, service that corresponds to the perfection of service itself, or the highest service: Sa vai pumsam paro dharmo yato bhaktir adhoksaje. Bhakti, therefore, is the supreme occupation (paro dharmah) of the living entity, because it is service performed directly in relation to God (adhoksaje). In the above verse, bhakti is correlated with dharma in its most essential and highest level. Bhakti, indeed, is the essence of dharma.

Conclusion

Thus we have seen that dharma finds its highest expression in bhakti, devotional service to God. We have also seen that bhakti is defined in terms of dharma, precisely because bhakti is the perfection of service—and dharma indeed does provide the full philosophical backdrop within which the experience of bhakti is properly understood. Through an examination of the ontological. sociological, and theological dimensions of dharma, we have been able to see how the concept of dharma functions in complex ways, signifying an understanding of reality that is profoundly comprehensive and virtually untranslatable, and therefore unfamiliar to the West. In the end, dharma as a concept is meant not merely to provide an exercise in philosophical discourse, but to be personally realized-and this is possible through the practice of bhakti.

GARUDA DASA is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago, in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations. He holds masters degrees in comparative theology from Chicago and Harvard.

Leave a Reply