Breaking the American Silence

A guru had never before gone onto the streets

and sung the names of God.

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

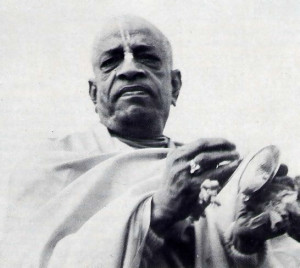

Srila Prabhupada had founded America’s first Krsna temple, initiated his first American disciples, and performed America’s first Vedic wedding. Now he was ready for another big step: America’s first public chanting of Hare Krsna by a genuine guru.

Srila Prabhupada had founded America’s first Krsna temple, initiated his first American disciples, and performed America’s first Vedic wedding. Now he was ready for another big step: America’s first public chanting of Hare Krsna by a genuine guru.

During the two months spent at 26 Second Avenue, Srila Prabhupada had achieved what had formerly been only a dream. He now had a temple, a duly registered society, full freedom to preach, and a band of initiated disciples. When a Godbrother had written asking him how he would manage a temple in New York, Prabhupada had said that he would need men from India but that he might find an American or two who could help. That had been last winter. Now Krsna had put him in a different situation: he had received no help from his God-brothers, no big donations from Indian business magnates, and no assistance from the Indian government, but he was finding success in a different way. These were “happy days,” he said. He had struggled alone for a year, but then “Krsna sent me men and money.”

Yes, these were happy days for Prabhupada, but his happiness was not like the happiness of an old man’s “sunset years,” as he fades into the dim comforts of retirement. His was the happiness of youth, a time of blossoming, of new powers, a time when future hopes expand without limit. He was seventy-one years old, but in ambition he was a courageous youth. He was like a young giant just beginning to grow. He was happy because his preaching was taking hold, just as Lord Caitanya had been happy when He had traveled alone to South India, spreading the chanting of Hare Krsna. Prabhupada’s happiness was that of a selfless servant of Krsna to whom Krsna was sending candidates for devotional life. He was happy to place the seed of devotion within their hearts and to train them in chanting Hare Krsna, hearing about Krsna, and working to spread Krsna consciousness.

Prabhupada continued to accelerate. After the first initiations and the first marriage, he was eager for the next step. He was pleased by what he had, but he wanted to do more. It was the greed of the Vaisnava—not a greed to have sense gratification but to take more and more for Krsna. He would “go in like a needle and come out like a plow.” That is to say, from a small, seemingly insignificant beginning, he would expand his movement to tremendous proportions. At least, that was his desire. He was not content with his newfound success and security at 26 Second Avenue, but was yearning to increase ISKCON as far as possible. This had always been his vision, and he had written it into the ISKCON charter: “to achieve real unity and peace in the world . . . within the members, and humanity at large.”

Swamiji gathered his group together. He knew that once they tried it they would love it. But it would only happen if he personally went with them. Washington Square Park was only half a mile away, maybe a little more.

Ravindra Svarupa: He never made a secret of what he was doing. He used to say, “I want everybody to know what we are doing.” Then one day, D-day came. He said, “We are going to chant in Washington Square Park.” Everybody was scared. You just don’t go into a park and chant. It seemed like a weird thing to do. But he assured us, saying, “You won’t be afraid when you start chanting. Krsna will help you.” And so we trudged down to Washington Square Park, hut we were very upset about it. Up until that time, we weren’t exposing ourselves. I was upset about it, and I know that several other people were, to be making a public figure of yourself.

With Prabhupada leading they set out on that fair Sunday morning, walking the city blocks from Second Avenue to Washington Square in the heart of Greenwich Village. And the way he looked—just by walking he created a sensation. None of the boys had shaved heads or robes, but because of Swamiji—with his saffron robes, his white, pointy shoes, and his shaved head held high—people were astonished. It wasn’t like when he would go out alone. That brought nothing more than an occasional second glance. But today, with a group of young men hurrying to keep up with him as he headed through the city streets, obviously about to do something, he caused quite a stir. Tough guys and kids called out names, and others laughed and made sounds. A year ago, in Butler, the Agarwals had been sure that Prabhupada had not come to the United States looking for followers. “He didn’t want to make any waves, Sally Agarwal had thought. But now he was making waves, walking through the New York City streets, headed for the first public chanting in America, followed by his first disciples.

In the park there were hundreds of people milling about—stylish, decadent Greenwich Villagers, visitors from other boroughs, tourists from other states and other lands—an amalgam of faces, nationalities, ages, and interests. As usual, someone was playing his guitar by the fountain, boys and girls were sitting together and kissing, some were throwing Frisbees, some were playing drums or flutes or other instruments, and some were walking their dogs, talking, watching everything, wandering around. It was a typical day in the Village.

Prabhupada went to a patch of lawn where, despite a small sign that read Keep Off the Grass, many people were lounging. He sat down, and one by one his followers sat beside him. He took out his brass hand-cymbals and sang the maha-mantra, and his disciples responded, awkwardly at first, then stronger. It wasn’t as bad as they had thought it would be.

Jagannatha: It was a marvelous thing, a marvelous experience that Swamiji brought upon me. Because it opened up a great deal, and overcame a certain shyness—the first time to chant out in the middle of everything.

A curious crowd gathered to watch, though no one joined in. Within a few minutes, two policemen moved in through the crowd. “Who’s in charge here’?” an officer asked roughly. The boys looked toward Prabhupada. “Didn’t you see the sign?” Swamiji furrowed his brow and turned his eyes toward the sign. He got up and walked to the uncomfortably warm pavement and sat down again, and his followers straggled after to sit around him. Prabhupada continued the chanting fur half an hour, and the crowd stood listening. A guru in America had never gone onto the streets before and sung the names of God.

After kirtana, he asked for a copy of the Srimad-Bhagavatam and had Hayagriva read aloud from the preface. With clear articulation, Hayagriva read: “Disparity in the human society is due to the basic principle of godless civilization. There is God, the Almighty One, from whom everything emanates, by whom everything is maintained, and in whom everything is merged to rest….” The crowd was still, Afterward, the Swami and his followers walked back to the storefront, feeling elated and victorious, They had broken the American silence,

* * *

Allen Ginsberg lived nearby on East Tenth Street. One day he received a peculiar invitation in the mail:

Practice the transcendental sound

vibration Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare,

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare,

This chanting will cleanse the dust from the mirror of the mind.

International Society for

Krishna Consciousness.

Meetings at 7A.M. daily.

Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 7P.M.

You are cordially invited to come and bring your friends.

Swamiji had asked the boys to distribute it around the neighborhood.

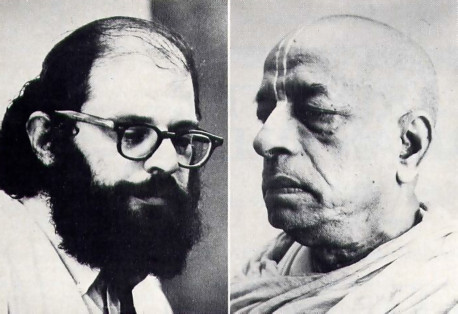

One evening, soon after he received the invitation, Allen Ginsberg and his roommate, Peter Orlovsky, arrived at the storefront in a Volkswagen minibus. Allen had been captivated by the Hare Krsna mantra several years before, when he had first encountered it at the Kumbha-mela in Allahabad, India, and he had been chanting it often ever since. The devotees were impressed to see the world-famous author of Howl and leading figure of the beat generation enter their humble storefront. His advocation of free sex, marijuana, and LSD, his claims of drug-induced visions of spirituality in everyday sights, his political ideas, his exploration of insanity, revolt, and nakedness, and his attempts to create a harmony of likeminded souls—all were influential on the minds of American young people, especially those living on the Lower East Side. Although by middle-class standards he was scandalous and disheveled, he was, in his own right, a figure of worldly repute, more so than anyone who had ever come to the storefront before.

Allen Ginsberg: Bhaktivedanta seemed to have no friends in America, but was alone, totally alone, and gone somewhat like a lone hippie to the nearest refuge, the place where it was cheap enough to rent.

There were a few people sitting cross-legged on the floor. I think most of them were Lower East Side hippies who had just wandered in off the street, with beards a curiosity and inquisitiveness and a respect for spiritual presentation of some kind.

Some of them were sitting there with glazed eyes, but most of them were just like gentle folk—bearded, hip, and curious. They were refugees from the middle class in the Lower East Side, looking exactly like the street sadhus in India. It was very similar, that phase in American underground history. And I liked immediately the idea that Swami Bhaktivedanta had chosen the Lower East Side of New York for his practice. He’d gone to the lower depths. He’d gone to a spot more like the side streets of Calcutta than any other place.

Allen and Peter had come for the kirtana, but it wasn’t quite time—Prabhupada hadn’t come down from his apartment. They presented a new harmonium to the devotees. “It’s for the kirtanas,” said Allen. “A little donation.” Allen stood at the entrance to the storefront, talking with Hayagriva, telling him how he had been chanting Hare Krsna around the world-at peace marches, poetry readings. a procession in Prague, a writers’ union in Moscow. “Secular kirtana,” said Allen, “but Hare Krsna nonetheless.” Then Prabhupada entered. Allen and Peter sat with the congregation and joined in the kirtana. Allen played harmonium.

Allen: I was astounded that he’d come with the chanting, because it seemed like a reinforcement from India. I had been running around singing Hare Krsna but had never understood exactly why or what it meant. But I was surprised to see that he had a different melody, because I thought the melody I knew was the melody, the universal melody. I had gotten so used to my melody that actually the biggest difference! hod with him was over the tune—because I’d solidified it in my mind for years, and to hear another tune actually blew my mind.

After the lecture, Allen came forward to meet Prabhupada, who was still sitting on his dais. Allen offered his respects with folded palms and touched Prabhupada’s feet, and Prabhupada reciprocated by nodding his head and folding his palms. They talked together briefly, and then Prabhupada returned to his apartment. Allen mentioned to Hayagriva that he would like to come by again and talk more with Prabhupada, so Hayagriva invited him to come the next day and stay for lunch prasadam.

“Don’t you think Swamiji is a little too esoteric for New York?” Allen asked. Hayagriva thought. “Maybe,” he replied.

Hayagriva then asked Allen to help the Swami, since his visa would soon expire. He had entered the country with a visa for a two-month stay, and he had been extending his visa for two more months again and again. This had gone on for one year, but the last time he had applied for an extension, he had been refused. “We need an immigration lawyer,” said Hayagriva. “I’ll donate to that,” Allen assured him.

The next morning, Allen Ginsberg came by with a check and another harmonium. Up in Prabhupada’s apartment, he demonstrated his melody for chanting Hare Krsna, and then he and Prabhupada talked.

Allen: I was a little shy with him because I didn’t know where he was coming from. I thought it was great now that he was here to expound on the Hare Krsna mantra—that would Sort of justify my singing. I knew what I was doing, but I didn’t have any theological background to satisfy further inquiries, and here was someone who did. So I thought that was absolutely great. Now I could go around singing Hare Krsna, and if anybody wanted to know what it was, I could just send them to Swami Bhaktivedanta to find out. If anyone wanted to know the technical intricacies and the ultimate history, I could send them to him.

He explained to me about his own teacher and about Caitanya and the lineage going back. His head was filled with so many things and what he was doing. He was already working on his translations. He always seemed to be sitting there just day after day and night after night. And I think he had one or two people helping him.

Prabhupada was very cordial with Allen. Quoting a passage from Bhagavad-gita where Krsna says that whatever a great man does, others will follow, he requested Allen to continue chanting Hare Krsna at every opportunity, so that others would follow his example. He told about Lord Caitanya’s organizing the first civil disobedience movement in India, leading a sankirtana protest march against the Muslim ruler. Allen was fascinated. He enjoyed talking with the Swami.

But they had their differences. When Allen expressed his admiration for a well-known Bengali holy man, Prabhupada said that the holy man was bogus. Allen was shocked. He’d never before heard a swami severely criticize another’s practice. Prabhupada explained, on the basis of Vedic evidence, the reasoning behind his criticism, and Allen admitted that he had naively thought that all holy men were one-hundred-percent holy. But now he decided that he should not simply accept sadhu, including Prabhupada, on blind faith. He decided to see Prabhupada in a more severe, critical light.

Allen: I had a very superstitious attitude of respect, which probably was an idiot sense of mentality, and so Swami Bhaktivedanta’s teaching was very good to make me question that. It also made me question him and not take him for granted.

Allen described a divine vision he’d had in which William Blake had appeared to him in sound, and in which he had understood the oneness of all things. A sadhu in Vrndavana had told Allen that this meant that William Blake was his guru. But to Prabhupada this made no sense.

Allen: The main thing, above and beyond all our differences, was an aroma of sweetness that he had, a personal, self-less sweetness like total devotion. And that was what always conquered me, whatever intellectual questions or doubts I had, or even cynical views of ego. In his presence there was a kind of personal charm, coming from dedication, that conquered all our conflicts. Even though I didn’t agree with him, I always liked to be with him.

Allen agreed, at Prabhupada’s request, to chant more and to try to give up smoking.

“Do you really intend to make these American boys into Vaisnavas?” Allen asked.

“Yes,” Prabhupada replied happily, “and I will make them all brahmanas,”

Allen left a $200 check to help cover the legal expenses for extending the Swami’s visa and wished him good luck. “Brahmanas!” Allen didn’t see how such a transformation could be possible.

(To be continued.)

From Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, by Satsvarupa dasa Gosvami. © 1980 by the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Leave a Reply