The Mantra-Rock Dance

January 1967: San Francisco. “The Avalon Ballroom seemed like a human field of wheat blowing in the wind—finally everyone was jumping, crying, shouting.”

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

Though some of the New York disciples had objected, Srila Prabhupada was still scheduled for the Mantra-Rock Dance at the Avalon Ballroom. It wasn’t proper, they had said, for the devotees out in San Francisco to ask their spiritual master to go to such a place. It would mean amplified guitars, pounding drums, wild light shows, and hundreds of drugged hippies. How could his pure message be heard in such a place?

Though some of the New York disciples had objected, Srila Prabhupada was still scheduled for the Mantra-Rock Dance at the Avalon Ballroom. It wasn’t proper, they had said, for the devotees out in San Francisco to ask their spiritual master to go to such a place. It would mean amplified guitars, pounding drums, wild light shows, and hundreds of drugged hippies. How could his pure message be heard in such a place?

But in San Francisco Mukunda and others had been working on the Mantra-Rock Dance for months. It would draw thousands of young people, and the San Francisco Radha-Krsna Temple stood to make thousands of dollars. So although among his New York disciples Srila Prabhupada had expressed uncertainty, he now said nothing to deter the enthusiasm of his San Francisco followers.

Sam Speerstra, Mukunda’s friend and one of the Mantra-Rock Dance organizers, explained the idea to Hayagriva, who had just arrived from New York: “There’s a whole new school of San Francisco music opening up. The Grateful Dead have already cut their first record. Their offer to do this dance is a great publicity boost just when we need it. It’s all been arranged. All the bands will be onstage, and Allen Ginsberg will introduce Swamiji to San Francisco. Swamiji will talk and then chant Hare Krsna, with the bands joining in. Then he leaves. There should be around four thousand people there.”

Srila Prabhupada knew he would not compromise himself; he would go, chant, and then leave. The important thing was to spread the chanting of Hare Krsna. If thousands of young people gathering to hear rock music could be engaged in hearing and chanting the names of God, then what was the harm? As a preacher, Prabhupada was prepared to go anywhere to spread Krsna consciousness. Since chanting Hare Krsna was absolute, one who heard or chanted the names of Krsna—anyone, anywhere, in any condition—could be saved from falling to the lower species in the next life. These young hippies wanted something spiritual, but they had no direction. They were confused, accepting hallucinations as spiritual visions. But they were seeking genuine spiritual life, just like many of the young people on the Lower East Side. Prabhupada decided he would go; his disciples wanted him to, and he was their servant and the servant of Lord Caitanya.

Mukunda, Sam, and Harvey Cohen had already met with rock entrepreneur Chet Helms, who had agreed that they could use his Avalon Ballroom and that, if they could get the bands to come, everything above the costs for the groups, the security, and a few other basics would go as profit for the San Francisco Radha-Krsna Temple. Mukunda and Sam had then gone calling on the music groups, most of whom lived in the Bay area, and one after another the exciting new San Francisco rock bands—the Grateful Dead, Moby Grape, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service—had agreed to appear with Swami Bhaktivedanta for the minimum wage of 250 dollars per group. And Allen Ginsberg had agreed. The line-up was complete.

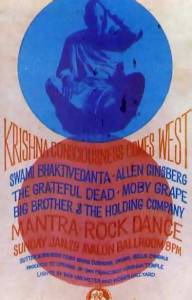

In San Francisco every rock concert had an art poster, many of them designed by the psychedelic artist called Mouse. One thing about Mouse’s posters was that it was difficult to tell where the letters left off and the background began. He used dissonant colors that made his posters seem to flash on and off. Borrowing from this tradition, Harvey Cohen had created a unique poster—KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS COMES WEST—using red and blue concentric circles and a candid photo of Swamiji smiling in Tompkins Square Park. The devotees put the poster up all over town.

With only a few days remaining before the Mantra-Rock Dance, Allen Ginsberg came to an early morning kirtana at the temple and later joined Srila Prabhupada upstairs in his room. A few devotees were sitting with Prabhupada eating Indian sweets when Allen came to the door. He and Prabhupada smiled and exchanged greetings, and Prabhupada offered him a sweet, remarking that Mr. Ginsberg was up very early.

“Yes,” Allen replied, “the phone hasn’t stopped ringing since I arrived in San Francisco.”

“That is what happens when one becomes famous,” said Prabhupada. “That was the tragedy of Mahatma Gandhi also. Wherever he went, thousands of people would crowd about him, chanting, ‘Mahatma Gandhi ki jaya! Mahatma Gandhi ki jaya!’ The gentleman could not sleep.”

“Well, at least it got me up for kirtana this morning,” said Allen.

“Yes, that is good.”

The conversation turned to the upcoming program at the Avalon Ballroom.

“Don’t you think there’s a possibility of chanting a tune that would be more appealing to Western ears?” Allen asked.

“Any tune will do,” said Prabhupada. “Melody is not important. What is important is that you chant Hare Krsna. It can be in the tune of your own country. That doesn’t matter.”

Prabhupada and Allen also talked about the meaning of the word hippie, and Allen mentioned something about taking LSD. Prabhupada replied that LSD created dependence and was not necessary for a person in Krsna consciousness. “Krsna consciousness resolves everything,” Prabhupada said. “Nothing else is needed.”

At the Mantra-Rock Dance there would be a multimedia light show by the biggest names in the art, Ben Van Meter and Roger Hillyard. Ben and Roger were expert at using simultaneous strobe lights, films, and slide shows to fill an auditorium with optical effects reminiscent of LSD visions. Mukunda had given them many slides of Krsna to use during the kirtana. One evening, Ben and Roger came to see Swamiji in his apartment.

Roger Hillyard: He was great. I was really impressed. It wasn’t the way he looked, the way he acted, or the way he dressed, but it was his total being. Swami, was serene and very humorous, and at the same time obviously very wise and in tune enlightened. He had the ability to relate to lot of different kinds of people. I was thinking, “Some of this must be really strange for this person—to come to the United States and end up in the middle of Haight-Ashbury with a storefront for an asrama and a lot of very strange people around.” And yet he was totally right there right there with everybody.

On the night of the Mantra-Rock Dance, while the stage crew set up equipment and tested the sound system and Ben and Roger organized their light show up stairs, Mukunda and others collected tickets at the door. People lined up all the way down the street and around the block waiting for tickets at $2.50 apiece. Attendance would be good, a capacity crowd and most of the local luminaries were coming. LSD pioneer Timothy Leary arrived and was given a seat onstage. Swami Kriyananda came, carrying a tamboura. A man wearing a top hat and a Suit with silk sash that said SAN FRANCISCO arrived, claiming to be the mayor. A the door, Mukunda stopped a respectably dressed young man who didn’t have ticket. But then someone tapped Mukunda on the shoulder: “Let him in. It’s all right. He’s Owsley.” Mukunda apologized and allowed Augustus Owsley Stanley II, folk hero and famous synthesizer of LSD, to enter without a ticket.

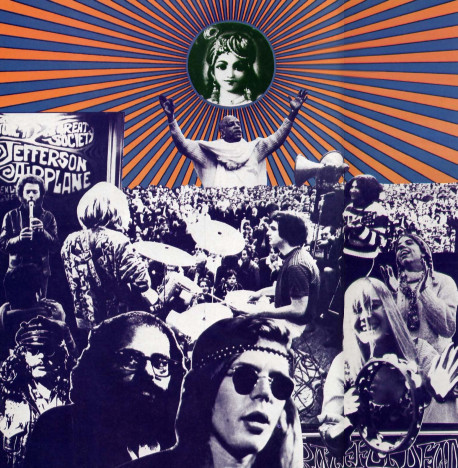

Almost everyone who came wore bright or unusual costumes: tribal robes, Mexican ponchos, Indian kurtas, “God’s eyes,” feathers, and beads. Some hippies brought their own flutes, lutes, gourd drums, rattles, horns, and guitars. The Hell’s Angels, dirty-haired, wearing jeans, boots, and denim jackets and accompanied by their women, made their entrance, carrying chains, smoking cigarette and displaying their regalia of German helmets, emblazoned emblems—everything but their motorcycles, which they had parked outside.

The devotees began a warm-up kirtana onstage, dancing the way Swamiji had shown them. Incense poured from the stage and from the corners of the large ballroom. And although most in the audience were high on drugs, the atmosphere was calm; they had come seeking spiritual experience. As the chanting began, very melodiously, some of the musicians took part by playing their instruments. The light show began: strobe lights flashed, colored balls bounced back and forth to the beat of the music, large blobs of pulsing color splurted across the floor, walls, and ceiling.

A little after eight o’clock, Moby Grape took the stage. With heavy electric guitars, electric bass and two drummers, they launched into their first number. The large speakers shook the ballroom with their vibrations and a roar of approval rose from the audience.

At ten o’clock Prabhupada walked up the stairs of the Avalon, followed by Kirtanananda and Ranacora. As he entered the ballroom, devotees blew conchshells, someone began a drum roll, and the crowd parted down the center, all the way from the entrance to the stage, opening a path for him to walk. With his head held high, Prabhupada seemed to float by as he walked through the strange milieu, making his way across the ballroom floor to the stage.

Suddenly the light show changed. Pictures of Krsna and His pastimes flashed onto the wall: Krsna and Arjuna riding together on Arjuna’s chariot, Krsna eating butter, Krsna subduing the whirlwind demon, Krsna playing the flute. As Prabhupada walked through the crowd, everyone stood, applauding and cheering. He climbed the stairs and seated himself softly on a waiting cushion. The crowd quieted.

Looking over at Allen Ginsberg, Prabhupada said, “You can speak something about the mantra.”

Allen began to tell of his understanding and experience with the Hare Krsna mantra. He told how Swamiji had opened a storefront on Second Avenue in New York and had chanted Hare Krsna in Tompkins Square Park. And he invited everyone to the Frederick Street temple. “I especially recommend the early-morning kirtanas,” he said, “for those who, coming down from LSD, want to stabilize their consciousness on reentry.”

Prabhupada spoke, giving a brief history of the mantra. Then he looked over at Allen again: “You may chant.”

Allen began playing his harmonium and chanting into the microphone, singing the tune he had brought from India. Gradually more and more people in the audience caught on and began chanting. As the kirtana continued and the audience got increasingly enthusiastic, musicians from the various bands came onstage to join in. Ranacora, a fair drummer, began playing Moby Grape’s drums. Some of the bass players and guitar players joined in as the devotees and a large group of hippies mounted the stage. Projected slides of multicolored oil slicks pulsed, and the balls bounced back and forth to the beat of the mantra, now projected onto the wall: Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. As the chanting spread throughout the hall, some of the hippies got to their feet, held hands, and danced.

Allen Ginsberg: We sang Hare Krsna all evening. It was absolutely great—an open thing. It was the height of the Haight-Ashbury spiritual enthusiasm. It was the first time there had been a music scene in San Francisco where everybody could be part of it and participate. Everybody could sing and dance rather than listen to other people sing and dance.

Janaki: People didn’t know what they were chanting for. But to see that many people chanting—even though most of them were intoxicated—made Swamiji very happy. He loved to see the people chanting.

Hayagriva: Standing in front of the bands, I could hardly hear. But above all, I could make out the chanting of Hare Krsna, building steadily. On the wall behind, a slide projected a huge picture of Krsna in a gold helmet with a peacock feather, a flute in His hand.

Then Srila Prabhupada stood up, lifted his arms, and began to dance. He gestured for everyone to join him, and those who were still seated stood up and began dancing and chanting and swaying back and forth, following Prabhupada’s gentle dance.

Roger Segal: The ballroom appeared as if it was a human field of wheat blowing in the wind. It produced a calm feeling in contrast to the usual Avalon Ballroom atmosphere of gyrating energies. The chanting of Hare Krsna continued for over an hour, and finally everyone was jumping and yelling, even crying and shouting.

Someone placed a microphone before Srila Prabhupada, and his voice resounded strongly over the powerful sound system. The tempo quickened. Srila Prabhupada was perspiring profusely. Kirtanananda insisted that the kirtana stop. Swamiji was too old for this, he said; it might be harmful. But the chanting continued, faster and faster, until the words of the mantra finally became indistinguishable amidst the amplified music and the chorus of thousands of voices.

Then suddenly it ended. And all that could be heard was the loud hum of the amplifiers and Srila Prabhupada’s voice, ringing out, offering obeisances to his spiritual master: “Om Visnupada Paramahamsa Parivrajakacarya Astottara-sata Sri Srimad Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Goswami Maharaja ki jaya! . . . All glories to the assembled devotees!”

Srila Prabhupada made his way offstage, through the heavy smoke and crowds, and down the front stairs, with Kirtanananda and Ranacora close behind him. Allen announced the next rock group.

The next morning the temple was crowded with young people who had seen Swamiji at the Avalon. Most of them had stayed up all night. Srila Prabhupada, having followed his usual morning schedule, came down at seven, held kirtana, and delivered the morning lecture.

Later that morning, while riding to the beach with Kirtanananda and Hayagriva, Swamiji half-audibly chanted in the back seat of the car, looking out the window as quiet and unassuming as a child, with no indication that the night before he had been cheered and applauded by thousands of hippies, who had stood back and made a great aisle for him to walk in triumph across the strobe-lit floor amid the thunder of the electric basses and the pounding drums of the Avalon Ballroom. For all the fanfare of the night before, he remained untouched, the same as ever in personal demeanor: he was aloof, innocent, and humble, while at the same time appearing very grave and ancient. As Kirtanananda and Hayagriva were aware, Swamiji was not of this world. They knew that he, unlike them, was always thinking of Krsna.

They walked with him along the boardwalk near the ocean, with its cool breezes and cresting waves. Kirtanananda spread the cadar over Swamiji’s shoulders. “In Bengali there is one nice verse,” Prabhupada remarked, breaking his silence. “I remember. ‘Oh, what is that voice across the sea calling, calling: Come here, come here. . .'” Speaking little, he walked the boardwalk with his two friends, frequently looking out at the sea and sky. As he walked he softly sang a mantra that Kirtanananda and Hayagriva had never heard before: “Govinda jaya jaya, gopala jaya jaya, radha-ramana hari, govinda jaya jaya.” He sang slowly, in a deep voice, as they walked along the boardwalk. He looked out at the Pacific Ocean: “Because it is great, it is tranquil.”

“The ocean appears to be eternal,” Hayagriva ventured.

“No,” Prabhupada replied. “Nothing in the material world is eternal.”

(To be continued.)

Leave a Reply