Indradyumna Swami sets out to find an ancient pilgrimage site of his spiritual tradition.

Hyderabad, India—Leaving the airport in a taxi headed for the local Hare Krsna temple, I was struck by familiar smells in the air. Fragrant flowers, pungent spices, a variety of incense and fruits all merged in the robust morning wind. Though not my first trip to India, this one was to take me to a place I had never known, a place, in fact, where few Westerners had ever gone. My destination was Ahovalam, a place of pilgrimage for devotees of Lord Krsna, a holy place high in the mountains of south India.

Ahovalam could not be found on official maps. I would need help to make the journey. With this in mind, I sought the advice of an old friend, Anandamaya dasa, with whom I had often traveled in the past. He was excited by the idea of seeing Ahovalam, and for my part I was glad to have him come along. He took me to meet local brahmana priests, who expressed concern for our safety. It would be an arduous journey, they said. Ahovalam lay three days to the south, perched high in the mountains amid rough terrain. The monsoon rains had just ended, and there was every chance that flood waters had damaged the roads.

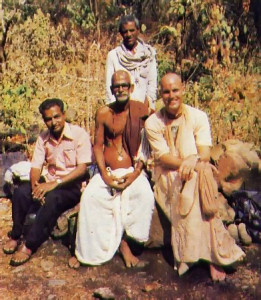

None of these apparent hardships could dissuade us, but one other obstacle almost ended our journey before it began: language. Neither I nor Anandamaya, who was French, spoke the regional dialect, Telegu, and without the possibility of verbal communication the trip seemed hopeless. Then, to our great relief, a friend of the Hare Krsna temple in Hyderabad, Mr. T.N. Srinivas, stepped forward and offered to act as our interpreter. He was director of the largest public school in the city and shared our excitement over visiting this ancient shrine of the Vaisnava (Krsna conscious) tradition. We secured provisions and started off early the next morning.

A Jungle Crossing

At dawn we boarded the first train heading south. There were no first-class places available, so we rode second class—that is, fifth class, since we ended up sharing our eight-seat compartment with twelve passengers, three chickens, and a stowaway goat. Time passed, and the Indian sun rose, bringing heat fatigue that nearly paralyzed us in our seats, until we made the obligatory connections to trains and finally a bus. As we went higher and higher into the mountainous region surrounding Ahovalam, the countryside rapidly changed. Soon everything was green and lush, the air easier to breathe. And then the jungle was upon us, thick and overpowering. Giant banyan trees towered over our heads, and huge palm leaves blocked the sky. It was another world, another age and dimension of nature. The further we advanced, the thicker the jungle grew. From my window I could see birds with exotic plumage and dozens of curious monkeys watching from the treetops. Here and there a deer, frightened by the sound of the motor, lept to safety.

“There are tigers also,” Mr. Srinivas noted, laughing. I didn’t see the humor. Finally the bus stopped. There was no more road. We got down and continued on foot. An hour later we arrived at Lower Ahovalam, a small village at the foot of the mountains. The villagers greeted us with enthusiasm. Although hundreds of thousands of pilgrims assemble each year at Benares and Allahabad to bathe in the sacred Ganges during important religious festivals, few brave the road to Ahovalam. The village brahmana invited us to his home and fed us an exquisitely simple yet delicious meal of krsna-prasada (vegetarian foods that have first been offered to Lord Krsna). Then he began relating the history of the sacred city Ahovalam. Night settled in around us with its sounds of nocturnal birds and animals. We sat back to hear his narration

A Formidable Atheist

“Several million years ago,” he began, “there lived an extraordinary being named Hiranyakasipu. The Puranas, the scriptural histories, describe that by executing severe austerities, he gained immense power, by which he tyrannized the universe. Vain and malevolent, he never hesitated to kill anyone who got in the way of his plans for wealth and material pleasures. No one could challenge him.

Nrsimhadeva and Laksmi, the goddess of

fortune, greets visitors to Lower Ahovalam.

“But Prahlada, his youngest son, did not share this demon’s atheistic views. A great devotee of the Lord since birth, Prahlada had no taste for child’s play or the pursuit of material pleasures. Rather, he bathed constantly in the ecstasy of divine consciousness and shared his spiritual wisdom with school friends whenever the occasion permitted. But Prahlada’s preaching greatly displeased Hiranyakasipu, who finally decided to destroy the child. Such devotion could not be allowed to survive. Nonetheless, despite all his efforts to kill the small boy, he was unable to do so. Prahlada was protected by the hand of God and hence invulnerable.

“‘Where is this God of yours?’ Hiranyakasipu demanded of the boy Prahlada. ‘Is He in my palace?’ he mocked, waving his sword towards a pillar. ‘Is he in this pillar?’

“‘Yes, father,’ the boy replied, ‘God is everywhere.’

Hiranyakasipu, his eyes red with rage then struck the pillar with his fist. From the pillar sprang instantly a terrible form of the Lord, half-man half-lion, to protect the small, devoted child. This form was called Nrsimhadeva, and He quickly killed the demonic king with His nails.

“The Supreme Lord is omnipresent,” the brahmana said, “and is capable of manifesting Himself wherever He wishes in whatever form He desires. It is therefore possible for Him to appear in such a marvelous form as Nrsimhadeva to annihilate the demonic and protect His devotees.”

Here the brahmana ended his narration. Now more eager than ever to begin our journey, we looked forward to actual seeing Ahovalam, renowned as the place where Lord Nrsimhadeva had emerged from the pillar to destroy the evil King Hiranyakasipu and protect the devoted Prahlada.

Temples in Caves

Rising the next morning before sunrise, we bathed and chanted our morning rounds of prayer beads. After a breakfast of rice and spiced vegetables, we took to the road. Our guide, a small man approaching sixty, led us through a tangled wilderness as though it were his backyard. As we penetrated the thick jungle, I noticed a small hatchet suspended from his belt. I was about to ask him what it was for when someone yelled to me from behind.

“Look out! A cobra! A cobra! “Before I could even react, the guide pushed me violently to the side of the thin trail and in one motion drew his hatchet and cut off the cobra’s head. I almost decided to turn back then and there. The day before, the guide said as we continued, he had dispatched a python more than twelve feet long. From that moment on, I was never more than two feet behind our hatchet-bearing guide. After a short climb, we came upon the first of nine temples dedicated to Lord Nrsimhadeva. Thick foliage covered the entrance. At first glance, the temple itself was indistinguishable from its surroundings, except for a few vague sculptures jutting out here and there.

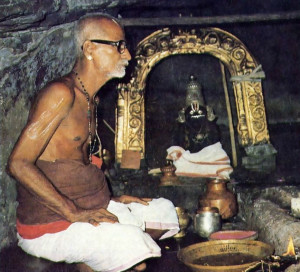

After cutting away the overgrowth, we entered the main room of the temple, which devotees thousands of years ago had carved completely out of the stone wall of the mountain. As we progressed, the light faded, until only an eerie green aura let us discern the ground under our feet. Dozens of bats, disturbed by our visit, flew furiously out over our heads. We lit our electric lamps and beheld the sanctuary’s beauty. Despite its incontestable antiquity, the original carvings and sculpted ceiling remained intact, protected by nature throughout the ages. As with most of the other temples we would visit that day, neither time nor the rampant vegetation had succeeded in erasing the extremely detailed craftsmanship that had gone into its creation.

On a raised stone platform before us stood majestically the Deity of Varaha-Nrsimha. Varaha, the boar incarnation of Lord Krsna, had killed Hiranyakasipu’s nefarious younger brother Hiranyaksa, and thus the two incarnations Varaha and Nrsimha had been installed together in this temple and worshiped for thousands of years. But gradually the inaccessibility of the place and the ever-growing wall of vegetation had discouraged pilgrims. Now only an occasional visitor still came to offer the Deities wild fruits or kunkuma powder.

All day long we progressed from one temple to another, crossing rope bridges suspended over deep ravines and rivers. At places where no path existed, we cut our way through the foliage and scaled high rocks. In each temple-cave a different Deity of Nrsimha awaited us: Karenca-Nrsimha, holding a bow: Chatravarta-Nrsimha, smiling broadly; Mahalola-Nrsimha, seated in the company of His eternal companion the goddess of fortune. At each temple, we paused to catch our breath and read from Srimad-Bhagavatam, an important Vedic scripture that recounts the history of Lord Nrsimhadeva.

At last, just over a ridge of high boulders, we arrived at a plateau formed by the debris of history. Here was an immense plain, said to be the site of Hiranyakasipu’s gigantic palace, its ruins exposed to the erosion of weather for hundreds and thousands of years. Dominating the landscape, poised fifteen stories high, was the famous ugra-stambha, described as the pillar from which Lord Nrsimhadeva had sprung to rid the earth of the formidable demon Hiranyakasipu. We stood transfixed by the sheer size of what lay before us. When whole, the palace must have stretched fifteen miles, judging by the pillar, which lay in two halves: one intact, the other fallen to the side.

Standing atop the ridge overlooking the relics of Ahovalam, I began to understand for the first time the meaning of antiquity. For many years my realization of Krsna consciousness as an ancient spiritual culture had been abstract and philosophical. Now that realization took a tangible form as I surveyed a scene described thousands of years ago in the sacred Vedic scriptures.

By dusk we had returned to Lower Ahovalam. Temple attendants completed their daily ceremonies as night slowly settled over the village. Families scurried home before dark, and we sorted our gear for the long ride back.

Leave a Reply