Back To Godhead Vol 22, 1969

|

by Nayana Bhiram

I AND THOU by Martin Buber, 137 pp., Scribner Library, $1.25.

THE WAY OF MAN (According to the Teachings of Hasidism) by Martin Buber, 41. pp.,CitadelPress.$.95.

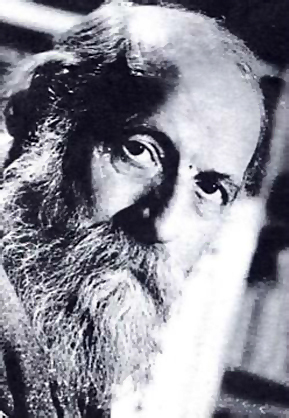

One of the best-known Jewish thinkers of recent times is Martin Buber. Called a poet, mystic and existentialist, the late professor has written a number of appreciations of Hasidism, a mystical Jewish folk movement begun in 18th century Europe, and far more widely read is his treatise on the “philosophy of dialog,” I AND THOU.

Before beginning the text of I AND THOU, the author cites the following line from Goethe: “So, waiting, I have won from you the end: God’s presence in each element.” The idea is supposedly not pantheistic, not that various items are gods, but that, according to Buber, “a divine spark lives in every thing and being, but each such spark is enclosed by an isolating shell.” How to find that spark and confront God directly is the problem, and not a new problem to be sure. Tennyson expressed it when, having plucked a “flower from the crannied wall,” he exclaimed in perplexity: “if I could understand what you are, root and all, and all in all, I should know what God and man is.”

Buber says one can know God through personal relationship—with either Nature, other men, or “spiritual beings.” Such a relationship is what Buber calls the “I and Thou” relationship. It is reciprocal, and therefore dialog.

The nature of reality is taken here to be twofold—or, rather, to be approachable in two distinct ways: The I-Thou relationship is meeting the world, supposedly as it is, with one’s whole being. It is contrasted with the relationship called “I-It.” The I-It relationship means taking the world as a tool for one’s own aggrandizement. Such a relationship applies to the false world of things to be used and possessed—a world within which most of us live. In I-It consciousness, I am not, paradoxically, an “I” but an “it”—another thing to be used. On the other hand, as I relate to Thou, I become truly I.

Needless to say, the I-Thou relationship is the more desirable of the two. Yet, although in Buber’s estimation it is a vehicle for love of God, at times I-Thou sounds more like an end. Nearly everyone wants to have a nice loving relationship with other living entities, and to feel love of God. Unfortunately, however, such a state of consciousness is not possible under the material concept of life, where everything is based on either immediate or extended self-interest and sense-gratification.

Buber’s method of exposition is not so clear and straightforward as he seems to believe it is. Speaking in the first person singular, at times the author assumes a pose of affected simplicity, like Khalil Gibran, in his “Prophet,” and at other times an abstrusely philosophical one resembling Nietzsche’s “Zarathushtra.” This pseudo-poetical style of spirituality no doubt accounts for much of the volume’s success. Most people think that mystical awareness means something misty and obscure—rather than clarity and light. And so, when an author speaks in vague spiritual commonplaces and platitudes, it is to be expected that he may attract a number of followers. To pin down more precisely what Buber is advocating, however, we must turn to his less known posthumous volume, THE WAY OF MAN.

A brief but concise exposition of Buber’s thoughts, THE WAY OF MAN is clearly a product of maturity as compared to his earlier I AND THOU. The author takes six Hasidic stories to illustrate the steps in attaining to “The Way”—the way to achieving God realization. This idea of The Way is, of course, borrowed from Taoism, to which Buber is indeed much indebted.

As far as the first step in God realization is concerned, Buber agrees with almost all spiritual authorities that it is to ask, Who am I? So long as a person does not venture onto this path of self-inquiry, he cannot hope to attain the perfection of life.

The second step is called here The Particular Way, and this means that each man has his own individual means of attaining the absolute. Buber asserts that God says, “whatever you do may be a way to me, provided you do it in such a manner that it leads you to me.” (Exactly where this tautologous quotation of God’s comes from is not explained.) “But what it is that can and shall be done by just this person and no other, can be revealed to him only in himself.”

In other words, what Buber is advocating here is what is known as “doing your own thing”—a popular doctrine, no doubt, but it can be spiritual suicide for anyone who is serious about self realization. For according to The Bhagavad Gita, which is one of the most widely revered texts covering the science of God realization, no progress can be made without surrendering oneself to a bona fide spiritual master. And, as long as one is engaged in devotional service to the Supreme Lord through the transparent medium of the spiritual master, it doesn’t matter what one’s specific activity is. In this way, though the Vedic standard does permit everyone to act according to his individual nature, it requires that that action first be dovetailed into devotional service under the master’s direction.

Thirdly, after advising one to do his own thing, Buber further advises the spiritual seeker to unify his soul, which is nothing less than to realize that soul means “the whole man, body and spirit together.” Buber’s lack of distinction here between body and soul is an error of serious significance, and can only be attributed to a poor fund of knowledge. Understanding that “I am not this body” is essential to the attainment of spiritual knowledge, and is the most elementary teaching of the Vedas: “Aham Brahmasmi”—I am Brahman, pure spirit soul.

In The Bhagavad Gita, Lord Sri Krishna explains the eternal nature of the soul to Arjuna, his pupil, in the following terms: “Never was there a time when I did not exist, nor you, nor all these kings, nor in the future shall any of us cease to be.” (2.12) So, according to authoritative scriptural sources, we learn that our true position is that of eternal spirit soul, that we are coeval parts and parcels, and servants, of the Supreme Lord.

The fourth and fifth points of Buber’s Way go together: making peace with oneself, and thus making peace with the world. This is a very nice sentiment. Psychologists have been trying since long before Freud to establish peace within man’s heart. And we have today the United Nations trying to make peace in the world. Both in vain. It is very easy for humanists like Martin Buber to advocate peace—individual and collective—but as for offering a practical method to attain it, they are completely baffled in their attempts.

Such a practical peace formula is offered, however, in the Gita Mahatma, an authorized commentary on The Bhagavad Gita: “Let there be one hymn for chanting, and let there be one occupation for the human race, namely transcendental loving service to the Lord.”

Buber’s last points are “not being preoccupied with the world,” rightfully understanding that the “earth is the Lord’s,” and thus hallowing it for God’s sake. Again, what is meant by “hallowing” is not explained, and it is doubtful whether the author himself knows. Like so many materialists who advocate dealing with the “here and now” of this earth, Buber fails to realize that this material world is only temporary and, in that sense, illusory. Not that it doesn’t exist, but that it is always changing, hence impermanent, and thus unreal. The point in Krishna Consciousness, the Vedic science of God realization, is to be attached neither to oneself nor to the material world, but only to Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. The material world is recognized in the light of such transcendental devotion to be only a manifestation of Krishna’s energy, and the true spiritual process is to go directly to the source.

Although an irnpersonalist, at times Buber does come close to the personalist conception. In his writing on Hasidism, he states that “God, no matter how infinite he is comprehended as being, is still Person and remains Person.” Were it otherwise it would not be possible for the I-Thou dialog between man and God to exist. Nevertheless, because Buber does not know very much about God as a person, his idea of dialog is quite roundabout. That is, one can “converse” with God through the medium of other entities. Why not directly, this reviewer wonders?

In the serious pursuit of God realization, which is really only another way of phrasing dialog with the Absolute, one can learn about the name, fame, and pastimes of the Supreme Lord. The Krishna Consciousness system, for example, follows the teachings of the Srimad Bhagwatam and other Vedic scriptures. Since God is non-different from His Name, one need only chant His Holy Names to associate with Krishna. The effect is blissful. As original Krishna conscious entities, we can attain our natural position of full knowledge, full bliss and eternity simply by associating with the Lord by chanting His Names: Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. This is a real, direct I-Thou relationship—and it is eternal, not fleeting like the chance meeting of eyes of a child and a cat, as Buber for some reason chooses to see it.

His Divine Grace A. C . Bhaktivedanta Swami has written: “God is situated in everyone’s heart. God is not away from us. He is present. He is so friendly that, in our repeated change of births, He remains with us. He is waiting to see when we shall turn to Him.” We have simply to turn to Krishna in order to revive our dormant love of Godhead, which has for so long remained buried within our hearts.

Leave a Reply