A dialogue

By Hayagriva Dasa (ISKCON New Vrndavana)

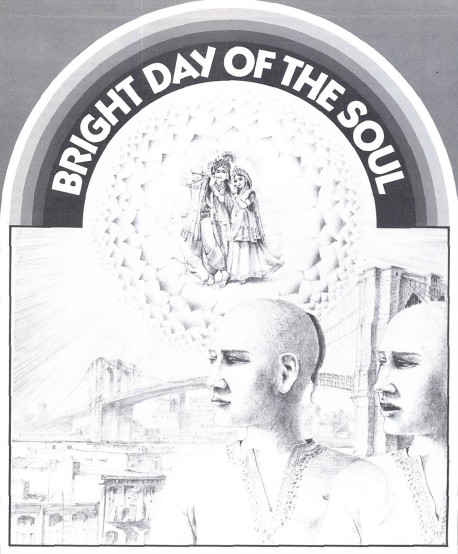

We stood on a rooftop in Manhattan, gazing out over the East River and the Brooklyn Bridge toward Brooklyn. His friend for many years, I asked him, “Do you actually love Krsna?” He thought for a second. “I love pleasure,” he said finally. “To be truthful.”

“Is Krsna giving you that pleasure?” I asked.

“Theoretically I admit that He is,” he said. “For I know that Krsna is the reservoir of all pleasure. But I often feel that the pleasure I’m taking is not to His liking.”

“To what do you attribute this?”

“Envy,” he said unhesitatingly. “He is infinite, and I am finite; He is powerful, and I am weak; He is opulent, and I am poor; He is beautiful, and I am brutish; He is famous, and I am insignificant; He is wise, and I am foolish; He can renounce everything, but I can deny myself nothing. Is there no wonder I am envious?”

“If He has all these qualities,” I asked him, “why don’t you love Him?”

“Because I cannot see Him,” he said.

“Why not?”

“Because I’m so unfortunate that I don’t want to. Because I’m so polluted that I can’t,” he said.

“Your position is pretty sorrowful,” I said. “What can I do about it?”

“Pray for me,” he said.

We fell silent for a moment. I watched the seagulls pivot about the bridge in white circles. We had come up dark and narrow stairs to the bright day at the top of the roof. I noticed that he automatically felt his back pocket.

“What are you looking for?” I asked.

“Checking,” he said. “My wallet.”

“Why ? “

“I’m afraid of losing it,” he said. “It’s my life savings.”

“But you said everything belongs to Him,” I laughed. “How can you lose anything that is not yours?”

“It’s not really mine,” he said. “It’s His. I’m simply afraid that He’ll take it from me.”

“Then you’re a thief,” I said. “A thief afraid of being caught. “

“You might say that,” he relented. “Whatever I have He’s slowly taking back because I’ve stolen it from Him. I have some beauty, but every day He is slowly taking that away. I have some strength, but the longer I live the less strength I have. When I was in college I felt that I was acquiring knowledge, but now not a day passes when I don’t feel myself more and more foolish. I used to think of myself as the center of the universe, the most important person alive, but now I only feel my insignificance as one of three billion people on a tiny planet destined to live only three score year and ten and to be buried in a grave that hardly lasts any longer. As you see, my friend, my position is not very enviable; therefore I envy.”

“But what of love?” I asked. “What of your capacity to love?”

“Whatever I love is simply a reflection of Him,” he said. “Because I can’t see Him, I love only reflections of Him. He is youthful, and therefore I love youth. He is all-knowing, and therefore I love knowledge. He is eternal; therefore I love life. He is blissful, and therefore I love pleasure. I would love only Him if I could but see Him, but I don’t deserve that benediction.”

“You seem conscious of Him,” I said. “Isn’t that at all auspicious?”

“Would you consider the position of one holding but a faded photograph of his lover an enviable position?” he asked. “I may see Him in the beauty of the sky, in a landscape, or in another person, or I may hear Him in a voice or in the lyrics of a popular song, or I may smell Him in the fragrance of gardenias or the musky twilight, or I may taste Him in the freshness of water or a just-cut melon, or I may touch Him when I feel someone beside me—but these are just memories. These are not Him.”

“Perhaps they are Him,” I suggested. “But perhaps He is teasing you.”

“Then He is a good teaser,” he admitted. “I often see myself running in circles like a dizzy schoolgirl, just waiting for Him to pay me a little mind.” He laughed at the image he had conjured of himself. “We are all female,” he said finally, “at least in respect to Him. He is the enjoyer, and we are the enjoyed. Isn’t it the position of the female to be enjoyed?”

“It is,” I agreed.

“Then in relation to Him we are all female,” he said. “He is always controlling, and we are always being controlled. Now what we have to learn is to enjoy being controlled. That is what the gopis enjoy—being controlled.”

“No one enjoys being controlled,” I said. “Surely you’re mistaken.”

“In all cases but love you’re right,” he said. “But in love we secretly want to be controlled. This is because we need direction, and we feel that the object of love can give us direction. Therefore love always concentrates on its eternality. When we love someone, we always feel, ‘I love you forever.’ In other words, ‘Love’s not time’s foot, though rosey lips and cheeks within his bending sickle’s compass come. Love alters not with these brief hours and weeks, but bears it out even to the edge of doom.’ If love is not forever, then it is not love. We all feel this in our love relations, and we ask no less from our lover but that he pledge eternal love. Practically speaking, though, isn’t this unreasonable to ask? Eternal love. Who is capable of that?”

“The eternal lover,” I smiled.

“Then that’s who we actually love,” he said. “Anyone other than that is but a poor substitute.”

“Who is the eternal lover?” I asked. “And what is He like?”

“Who is the eternal lover?” I asked. “And what is He like?”

“He is male,” he said. “And He is but a youth.”

“The eternal father?”

“The eternal father,” he repeated. “He is a youth, and yet He is the eternal father. We think of Him as old, and indeed He is the oldest, but because of this we think that He is an old man, and this is all due to our thinking of Him as an ordinary person. He is the oldest, but He is eternally young, just like an adolescent boy.”

“You speak of the Eternal Boy,” I said, “but I want to see the eternal girl. It is she who interests me.”

“She is His,” he said. “Why should she be interested in you when she has Him?”

I did not answer. We looked a long time at the long rows of buildings before us and through the hot haze of cars moving slowly along the shores of Brooklyn.

“These bodies of ours are like flashes,” he mused. “We no sooner cultivate them but they grow old and diseased, and they die. We no sooner learn to enjoy ourselves here than we are quickly taken away. All we need know is that whatever we see in the world that is beautiful or magnificent is but a reflection of Him. We need not even think in terms of him and her, as Sukadeva Gosvami did not even perceive sexual distinctions but saw all creatures as living entities, intimately part of Him. The great sages travel through life without losing a glimpse of His presence. In comparison to them, we are like confused children, running from this object to that for satisfaction. Instead of satisfaction, all we find is pain, pain inflicted by other living entities, by nature and by our own minds and bodies. All we want is to drink the waters of satisfaction, but all we get are the waters of discontent. All we seek is the nectar of His lotus feet, but all we get is the bile of our own doubt. Because we are weak, we have ceased to even search for Him. Because we are deaf, we have ceased to even hear of Him. Because we are callous, we have ceased to even feel Him. Because we are poor, we have ceased to even hope for Him, and because we are not renounced, we have forgotten Him. Our only hope is that out of pity He will turn His lotus eyes to us, and out of pity He will allow us to glimpse the waters of the Yamuna River where He bathed and splashed with His feet. Our hopes may not seem realistic, but they are great because they are directed to the great. We have no conception of how great He is. We can only think of this one body, or one nation, or one planet, or one universe. But simply with one exhalation innumerable universes emanate from the pores of His skin, and with one inhalation they all return to His body, and in this way the entire cosmic creation is manifest and annihilated according to a time cycle beyond our powers of comprehension, for universal time loses all significance in the face of what we have to call eternity.”

“These bodies of ours are like flashes,” he mused. “We no sooner cultivate them but they grow old and diseased, and they die. We no sooner learn to enjoy ourselves here than we are quickly taken away. All we need know is that whatever we see in the world that is beautiful or magnificent is but a reflection of Him. We need not even think in terms of him and her, as Sukadeva Gosvami did not even perceive sexual distinctions but saw all creatures as living entities, intimately part of Him. The great sages travel through life without losing a glimpse of His presence. In comparison to them, we are like confused children, running from this object to that for satisfaction. Instead of satisfaction, all we find is pain, pain inflicted by other living entities, by nature and by our own minds and bodies. All we want is to drink the waters of satisfaction, but all we get are the waters of discontent. All we seek is the nectar of His lotus feet, but all we get is the bile of our own doubt. Because we are weak, we have ceased to even search for Him. Because we are deaf, we have ceased to even hear of Him. Because we are callous, we have ceased to even feel Him. Because we are poor, we have ceased to even hope for Him, and because we are not renounced, we have forgotten Him. Our only hope is that out of pity He will turn His lotus eyes to us, and out of pity He will allow us to glimpse the waters of the Yamuna River where He bathed and splashed with His feet. Our hopes may not seem realistic, but they are great because they are directed to the great. We have no conception of how great He is. We can only think of this one body, or one nation, or one planet, or one universe. But simply with one exhalation innumerable universes emanate from the pores of His skin, and with one inhalation they all return to His body, and in this way the entire cosmic creation is manifest and annihilated according to a time cycle beyond our powers of comprehension, for universal time loses all significance in the face of what we have to call eternity.”

“He exists in eternity?” I asked.

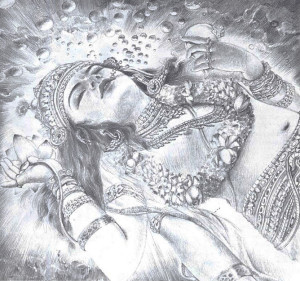

“Eternity exists in Him,” he said, “for it was never without Him. We cannot imagine His beginning. That is not possible, for He is adi-purusa, the primeval person, the first progenitor, the unmoved mover, the cause of all causes, the beginning, middle and end of all beings, the mighty God and everlasting Father of all. His greatness we cannot imagine, but we should not be concerned with this. The gopis, the cowherd girls of Vrndavana, do not recognize Him as such, as the almighty Godhead, but as a boy beloved by them. For them He is not Yahweh, whose name is unspoken, nor a burning bush, nor a voice from the mountain, nor a thunderbolt, nor the multi-handed Maha-Visnu, nor Narayana with all opulences, nor the great Allah, nor the triumphant Messiah, but a young boy named Krsna who simply tends the cows, plays His flute and dances. For the gopis there is no one more beautiful than He, nor anyone as merry, or, for that matter, as wise. Above all, He knows how to make them mad for Him. During the rasa dances He would disappear, and the gopis would wander about the forests of Vrndavana calling for Him. How little they cared about God! Being young country girls, they did not even think of God. Their thoughts were always with Krsna, their friend. Once, when they found Him in the woods waiting for Radharani, He played a trick on them by spouting two extra arms and appearing in His form as Lord Narayana. When the gopis approached Him, they offered their obeisances out of formality and then quickly excused themselves to run off and continue looking for Krsna. They saw Narayana, God, in the woods, but they were so eager to find Krsna that they simply passed Him by. The gopis were not great theologians or philosophers, though we understand that in their previous lives they were great sages, and they manifested themselves as cowherd girls in Vrndavana in order to relish a love relationship with Krsna. As gopis their one obsession was Krsna. Nor did they think of Him philosophically as the embodiment of all spiritual qualities. To them He was just Krsna, the boy with the lotus eyes, the friend whose flute charmed them, Krsna, their most dearly beloved. Their only reward for loving Him was that love itself and the anguish of separation, but separation was even more relishable than meeting, if such could be, for in separation they thought of Him constantly. Every object that met their gaze reminded them of Him. Their minds pondered His form and recalled His words. Upon hearing a flute they would swoon, and the sight of a peacock would make them mad with ecstasy. For Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who longed for Krsna as Radha, every stream and rivulet was the River Yamuna, and every flower and bee had a story to tell about Krsna. The animals somehow knew of Him secretly, but they would not divulge His whereabouts or their own knowledge of Him. Who can imagine the ecstasy of the gopis when Krsna left Vrndavana? Some even threw themselves under the wheels of His chariot, imploring Him not to leave for the city life of Mathura. In the absence of Krsna, the gopis constantly wept, wondering when He would return and discussing His activities amongst themselves. Lord Visnu was always being worshiped by demigods like Siva, Brahma, Indra, Candra and others, but when Krsna walked through the forests of Vrndavana, only the cowherd boys walked with Him. He took pleasure in calling the cows and in playing His flute and sometimes in running and wrestling with the cowherd boys. When He walked the banks of the Yamuna, He was always garlanded with many forest flowers, and His body was smeared with the pulp of sandalwood and tulasi leaves. The aroma surrounding Him attracted the bees, and they would hum about Him when He played His flute so that it seemed they were performing together. When His flute sounded in the woods, all the animals would stand still and even cease chewing grass to listen carefully. Even the fish and birds appeared stunned by the sounds. Sometimes Krsna was accompanied by Balarama, His elder brother, who appeared almost as attractive as Krsna Himself. After a day in the fields with the cows, Krsna would return home like the moon arising in the evening. Sometimes it would appear that He was a little fatigued from His vigorous day, but He would swagger into His home with a large stride, and all men, women and cows would immediately forget their hardships. After Krsna had left Vrndavana for Mathura, the cowherd girls would remember how He embraced them and talked with them, smiling sweetly, after the rasa dance in the forests of Vrndavana. Sometimes His face would be smeared with the dust raised by the hooves of the cows, and this made Him all the more attractive to them. What did they care for Narayana and all His jeweled opulence? They only thought of Krsna and His moving eyes and remembered His words and their sweet times with Him. The gopis wept throughout the night before He left, and they watched His chariot as long as possible until it faded from sight. They remained standing still like painted pictures, watching the dust of His chariot in the distance. Then they returned to their homes and simply thought of Him day and night. Of all the gopis, Radharani was most grief-stricken. Once She took a bumblebee to be Krsna’s messenger and began to talk to it. She accused the bumblebee of being like his master Krsna, in that the bee’s habit was to sit on a flower, take a little honey from it and immediately fly away to taste another flower. ‘Krsna gives us the chance to taste the touch of His lips, and then He leaves us altogether,’ Radharani lamented. Thus the gopis pined like school girls while Krsna was away from them. Now He is gone from us, or somehow we have lost Him, and it’s our great tragedy that we cannot even remember or long for Him. If we cannot shed tears for Him, then we should shed tears because we cannot weep. Now we are suffering because we’re trying to find some way to forget Him completely. We run from object to object to avoid Him, but eventually everything parts from us, and we are left with either the thought of Him or the thought of our own death. Yes, if we are left without a thought of Him, He comes for us as death. He Himself says that for those who have forgotten Him, He comes as death to take everything away. But even then we have the freedom to turn from Him, for that freedom He never denies us.”

“The freedom to turn to Him or avoid Him?” I asked.

“The freedom to love Him or not,” he replied. “For without freedom there can be no love. If I were God, I could certainly force you to love me, but that would not be love. Love is not forced by someone exterior. Love is response, relationship, communication. Love is the assertion of our being, of our essence as living entities. If we were not allowed freedom to love, we would be puppets only. There is Krsna and His creation; Krsna is complete in Himself, and the creation is complete in itself. All the qualities that are in Krsna, including the quality of freedom, are also in the creation in minute quantity. Now we must understand that as His creation, we are meant to give Him pleasure, and in giving Him pleasure, we receive it in return. But who knows of this? We have fallen, and our concern is now just with ourselves. We are like the chained prisoners of Socrates’ cave, enjoying the pageant of shadows about us, content with squinting in the darkness.”

“We need direction,” I said. “Without it we’re bound to the cave and the cycles of birth and death.”

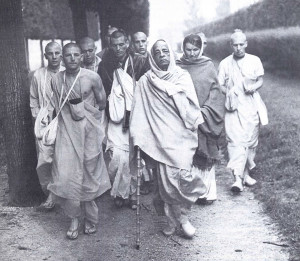

“The spiritual master has come within the cave singing His names,” he said. “And now he’s leading us out. We must be careful not to hide in the crevices or to lose his voice around the dark corners. We have to listen, not lose his voice, and hasten in the dark after him, trusting that he is leading us out into the light, for he has come from the light and knows the way. Is there any other who knows our destination? We may think we know our position on a map, but who knows the destination of mankind? Where are we going? What was our past? We can’t even remember the past events in this our present life, but Krsna tells Arjuna, ‘Many, many births both you and I have passed. I can remember all of them, but you cannot.’ And He also tells Arjuna that there was never a time when He did not exist, nor Arjuna, nor all the kings at Kuruksetra, nor that in the future any of them shall cease to exist. Krsna tells us clearly of our eternality and destination, and if His song is too lofty for our comprehension, if we cannot hear it in the depths of the cave amidst the panoramas of shadows projected by desire, the spiritual master actually descends to guide us. Our destination is beyond the irreversible succession of events through which we pass out of that cave. Our destiny indeed is to leave that cave, and to arrive. Our journey is our actual evolution, our soul’s evolution through material bodies that but serve us in our escape. Our soul’s progress is symptomized by consciousness, and in its highest state the soul is conscious of Krsna, of its ultimate destination, of its home.”

“The spiritual master has come within the cave singing His names,” he said. “And now he’s leading us out. We must be careful not to hide in the crevices or to lose his voice around the dark corners. We have to listen, not lose his voice, and hasten in the dark after him, trusting that he is leading us out into the light, for he has come from the light and knows the way. Is there any other who knows our destination? We may think we know our position on a map, but who knows the destination of mankind? Where are we going? What was our past? We can’t even remember the past events in this our present life, but Krsna tells Arjuna, ‘Many, many births both you and I have passed. I can remember all of them, but you cannot.’ And He also tells Arjuna that there was never a time when He did not exist, nor Arjuna, nor all the kings at Kuruksetra, nor that in the future any of them shall cease to exist. Krsna tells us clearly of our eternality and destination, and if His song is too lofty for our comprehension, if we cannot hear it in the depths of the cave amidst the panoramas of shadows projected by desire, the spiritual master actually descends to guide us. Our destination is beyond the irreversible succession of events through which we pass out of that cave. Our destiny indeed is to leave that cave, and to arrive. Our journey is our actual evolution, our soul’s evolution through material bodies that but serve us in our escape. Our soul’s progress is symptomized by consciousness, and in its highest state the soul is conscious of Krsna, of its ultimate destination, of its home.”

We looked out again across the rooftops toward Brooklyn. The city was hot and seemed to be roaring in pain about us, like an enraged bull. A blast of heat from the streets, of deadly fumes, swept up like an angry sigh.

“After all,” he said, “Home is not so different from what we expected—a quiet and simple place in the country with lots of trees and cows, and Him there, ready to play, stopping and waiting for us.”

Leave a Reply