by Bibhavati-devi dasi

Adapted from Srimad-Bhagavatam, translation and commentary by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

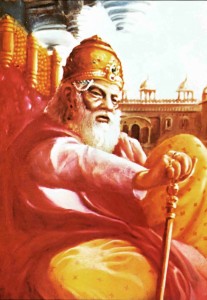

With recent disgrace of an American president still fresh in our minds, it is interesting to read of a similar case in ancient times. Five thousand years ago, a blind king named Dhrtarastra dishonored his high post and caused the death of millions. His story is of special importance, even today, because he found an antidote to the crimes of a lifetime, and in his old age became self-realized.

With recent disgrace of an American president still fresh in our minds, it is interesting to read of a similar case in ancient times. Five thousand years ago, a blind king named Dhrtarastra dishonored his high post and caused the death of millions. His story is of special importance, even today, because he found an antidote to the crimes of a lifetime, and in his old age became self-realized.

King Dhrtarastra was the acting monarch of Hastinapura, the capital of the Vedic kingdom of Bharata, which five thousand years ago (according to the Vedic literature) spread over most of the planet. Hastinapura was on the banks of the Yamuna River, at the site of present-day Delhi. As its name indicates (hasti means “elephant”), it was a city full of opulently decorated elephants. Noblemen rode elaborate chariots past marble palaces inlaid with glittering jewels. The sweet smell of incense drifted out of latticed windows. Trees bearing fruits and flowers lined the wide streets, which were sprinkled with scented water. There was no hint of poverty or distress. Hastinapura was the crown jewel of the abundant Vedic civilization.

From the beginning, Dhrtarastra’s position as king was never legal, for he was blind, and Vedic law ruled that a blind man could not be king. Thus the throne went to his younger brother Pandu. But when Pandu died in his young manhood, Dhrtarastra began ruling on behalf of Pandu’s five sons, who were still children. In an age of great and honorable kings, Dhrtarastra was an exception. Swayed by his eldest son Duryodhana’s ruthless lust for power, Dhrtarastra began to abuse the guardianship of the Pandavas by closing his already-blind eyes to the planned and purposeful efforts of Duryodhana to destroy the boys.

As the descendant of a great royal dynasty, Dhrtarastra had the lineage and rearing of a proper monarch. But it seemed that he was as blind spiritually as he was physically. Although he admired and even loved the five fatherless princes, he began to contemplate taking away their kingdom and even their lives.

Yet Dhrtarastra was not simply a ruthless monster preying on defenseless youths. There were great paradoxes in his nature. On the one hand, he appreciated the good counsel of his saintly younger brother, Mahatma Vidura. On the other hand, he was weak enough to be swayed by his attachment to a son whom he knew to be dishonorable. Like many of us, though he knew right from wrong he felt powerless to stem the relentless tide of events—events that were to sweep him across the border between good and evil into a disastrous war.

Full of envy, the young Duryodhana and his brothers (the Kuru princes) watched their five cousins growing day by day into energetic, effulgent personalities loved by everyone. Yudhisthira, the eldest, was heir to the throne, and as he approached manhood, Duryodhana decided to murder him, his four brothers, and their mother, Queen Kunti. Boyish rivalry had developed into a struggle for survival.

We do not know what doubts and guilts were in the mind of the old blind king when he heard the treacherous suggestions of his eldest son and his cunning ministers. But he liked something of what he heard. He himself wanted to seize the throne. So Dhrtarastra asked the Pandavas and their mother, Queen Kunti, to visit a nearby city named Varanavata. There the conspirators planned to finish them off.

In the very presence of sympathetic figures like Vidura and Bhisma, the innocents were beset by a peril they could neither foretell nor fight against. Only the power of a few telling words from Mahatma Vidura startled them into a realization of Dhrtarastra’s treachery. As the five heroic youths were leaving Hastinapura with their beautiful and noble mother, Queen Kunti, Vidura spoke some enigmatic words that eluded the rest of the royal family. His words were meant only for the ears of Yudhisthira.

“A weapon not made of steel or any other material element can be more than sharp enough to kill an enemy,” Vidura said. “He who knows this is never disturbed. Fire cannot extinguish the soul; it can merely annihilate the material body.” Although Mahatma Vidura habitually lectured the royal family about spiritual matters, Queen Kunti was puzzled by these words. “What did he mean?” she later asked Yudhisthira, and he explained to her precisely what Vidura had meant. The fine residential palace at Varanavata was to be their funeral pyre. They did in fact find that the walls of the new palace were made of combustible materials and shellac. Fire would be the weapon lurking in the walls of their new home.

When you are young and strong, no future seems altogether bleak. The Pandavas lived hopefully in the palace of shellac for almost a year. Then, one night, Vidura came to them in disguise and informed them that the housekeeper was going to set fire to the house on the fourteenth night of the waning moon. Dhrtarastra had been biding his time, but now the Pandavas remembered with a jolt that he really intended to assassinate them.

In an intricately plotted escape, the Pandavas entered a tunnel under the house, and as the house burned down they fled into the forest.

When Dhrtarastra heard of the supposed death of his five nephews and their mother, he performed the funeral rites with great cheerfulness. The only other cheerful face was that of Vidura, who knew the facts.

While Dhrtarastra and Vidura smiled and the relatives mourned, the Pandavas wandered in the forest, wondering how they had come to this predicament. Bhima used his strong body to protect his mother, Kunti, and his brothers from all sorts of calamities. They took to begging for food and eventually disguised themselves as brahmans. The simple white dress of brahmans, however, could not cover the hearts of these warriors. When the Pandavas heard of the marriage contest for the Pancala princess, Draupadi, they were determined to see this wonderful event.

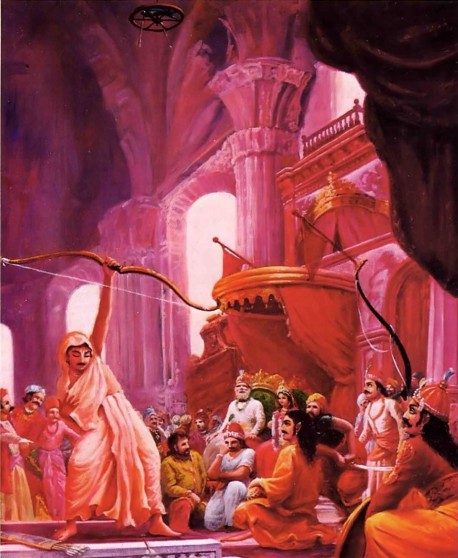

Draupadi had wanted to marry Arjuna, the most skillful bowman among the Pandavas, and her father had therefore contrived a test so difficult that only someone of Arjuna’s greatness could pass it. The target was a fish hanging near the high ceiling of the palace. Just under it hung a wheel. The aspiring archer had to pierce the fish’s eye through the spokes of the protecting wheel. Moreover, he’d have to do this without looking at the target! On the ground was a water pot in which the fish and the wheel were reflected. The contestant had to fix his aim on the target by looking at the trembling water in the pot. Everyone was astonished when Arjuna, in the dress of a poor brahman, pierced the target. The contending princes offered stiff resistance to Arjuna, but he fought them off and gained the hand of Draupadi.

Arjuna took his new bride home to the humble but where he stayed with his mother and brothers. On arriving, he called out joyfully for them to come and see his prize. Kunti, thinking that Arjuna had obtained something to eat on his begging rounds, did not come out, but said, “Whatever you have, you must share it equally with your brothers.” In this unusual way, Draupadi became the wife of not one but all five of the young princes.

The hard days of living in a bamboo hut now passed away like a dream. All at once the Pandavas’ fortunes changed with the startling speed of an arrow winging to its target. They took Draupadi, who was a wealthy and powerful princess, back with them to Hastinapura and set up residence at Indraprastha, a nearby city. Then they built a glittering palace with a mysterious defense system designed to bewilder enemies. The people of the kingdom worshiped the young princes as heroes, and they soon had amassed so much wealth and subordinated so many lesser princes that Yudhisthira decided to hold a Rajasuya sacrifice.

This sacrifice was a battle cry of sorts, since it required that all lesser kings and princes pay taxes to support the cost of the elaborate ceremony. King Yudhisthira (who was known as aja-satru, or one who has no enemies) fortunately had only one dissenting king, Jarasandha, to deal with before he could declare himself qualified to hold the sacrifice and in effect become the emperor of the world.

If Yudhisthira was to be the most powerful king in the world, it was not for his own sake that he wanted to proclaim it. His real motive was to invite Lord Krishna and please Him by offering Him the worship reserved for the most exalted person in the assembly.

King Yudhisthira, who was honor personified, invited all the elders: his teacher Dronacarya, Bhisma (the grandfather of the Kurus), Mahatma Vidura, and Dhrtarastra. He also invited Duryodhana and all the other sons of Dhrtarastra. Kings came from all over the world, and the ordinary citizens also visited the ceremony. In that setting the Pandavas openly declared to everyone that Lord Krishna was the Supreme Lord, and they offered Him their worship. However, a trace of viciousness marred the luxuriant sacrifice. When Duryodhana saw that Yudhisthira had become overwhelmingly more famous and opulent than he, he began to burn with jealousy. He allowed his pride to poison everything he saw in connection with the Pandavas. Even the artful construction of Yudhisthira’s new palace only kindled his rage. The defense system outside the castle consisted of moats so designed that it was impossible to tell water from dry land. Duryodhana approached some water, thinking it to be land, and fell in. Krishna’s queens laughed at him, but Duryodhana did not take it as a joke. His hair standing on end in anger, Duryodhana immediately left the palace in silence, with his head bowed. King Yudhisthira felt sorry, for he knew that inevitably this incident would increase the enmity between the two wings of the Kuru dynasty.

Soon afterward, Dhrtarastra sent Yudhisthira an invitation to a gambling match. Yudhisthira well knew that this gambling match was meant to destroy him. Unhappily, he accepted the challenge; as a prince he could not honorably refuse. Duryodhana had asked Sakuni, a notorious cheater, to play dice with Yudhisthira. Very early in the game, Yudhisthira realized that Sakuni was cheating. His moral integrity, however, forced him to continue the game until Sakuni had won everything—including Yudhisthira’s wealth, his kingdom, and even his wife, Draupadi. In a painful scene, Duryodhana’s brother Duhsasana tried to strip Draupadi naked in front of the assembled warriors. We cannot imagine how shocking this act was to the chaste queen and her chivalrous husbands. Helplessly, Draupadi called on the Supreme Person, Lord Krishna. By His mystic power, Krishna lengthened her sari without limit, so that Duhsasana was unable to fully humiliate her. This tense scene was a seed that grew in time into the catastrophic Battle of Kuruksetra.

As a result of the gambling match, Duryodhana banished the Pandavas to the forest for twelve years. He promised them that if they could spend the thirteenth year incognito, without being discovered by anyone, he would give back their kingdom. That feeble promise from their dangerous enemy was a shaky claim to the throne. But they had no other recourse. So, empty-handed, they walked out of Hastinapura into the shadow of exile. For twelve years they lived in the forest with Draupadi, and they also managed to survive the thirteenth without being discovered. Then they went to Hastinapura and reminded Dhrtarastra of his son’s promise to return their kingdom. Dhrtarastra, whose character wavered between candor and mean trickery, tried to deny that promise. Finally, the Pandavas asked for only five villages to rule, one for each of them. According to the Vedic code of behavior for a warrior, they could not accept employment or go into business, but had to be rulers of some kind. Then, with no objection from Dhrtarastra, Duryodhana said that he would not give them enough land to push a pin into. With that flippant remark, Duryodhana created a deadlock. The Pandavas had no kingdom. But Lord Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, wanted the pious Pandavas to be more powerful than Dhrtarastra and his sons. So now they had no recourse but to fight.

According to Vedic sources, the resulting battle—the famous Battle of Kuruksetra—lasted for 18 days and took 640 million lives. Such a massacre as a result of a vendetta between two parts of one family may seem impossible. Yet the ancient records describe in considerable detail atomic weapons that could decimate entire armies. This great battle, although it took place five thousand years ago, involved weapons more subtle and more deadly than those that modern scientists have developed. Although the contending warriors rode in chariots drawn by horses, they could shoot (by mantra) arrows that could find a specific target. Huge elephants fell down like cut trees before air, water, and fire weapons unknown today.

When the storm of destruction finally abated, Dhrtarastra was left with nothing but his burning conscience and his good wife, Gandhari. They had lost all their sons and grandsons. All the principal soldiers killed in the battle were related in some way or another; therefore the family members mourned together. Maharaja Yudhisthira, far from acting like a conqueror, felt great remorse. He was very conscious of his duty toward Dhrtarastra and Gandhari, and he took care of them both in royal style.

An indication of King Yudhisthira’s glorious character is that he felt the battle of Kuruksetra to be his fault, even though the errors of Dhrtarastra were colossal. For his part, Dhrtarastra settled into the role of the honorable royal uncle, somehow resigning his conscience to the fact that because of his decision, millions of people had died within a few days.

Fortunately, while Dhrtarastra was grasping at a life of skin-deep respectability, Vidura, his younger brother, returned to the palace after some years of pilgrimage. When he saw Dhrtarastra living comfortably in the palace of Yudhisthira and callously forgetting his former acts of aggression, Vidura’s saintly attitude turned hard as steel. Sadhu (“saint”) means “one who cuts.” So, with words, the sadhu Vidura began to cut away the false sense of security which Dhrtarastra felt as he sat in the gorgeous palace of his nephew. Vidura saw that Dhrtarastra was accepting the hospitality of Yudhisthira because he did not know what else to do. As his life passed imperceptibly away, Dhrtarastra spent his old age in casual ease, surrounded by what was left of his family. To Vidura this looked like a crisis, and he compassionately began to talk to him: “My dear king, please get out of here immediately. Do not delay. The Personality of Godhead in the form of time is approaching us all. Under the influence of time you must surrender your life, what to speak of other things, such as wealth, honor, children, land, and home.” Vidura wanted to point out to Dhrtarastra that the human form of life is meant for seeking the shelter of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. So he spoke abrasively, trying to bring him to his senses. “You have been blind from your very birth, and recently you have become hard of hearing. Your memory is shortened, and your intelligence is disturbed. Your teeth are loose, your liver is defective, and you are coughing up mucus.” He encouraged the aging king, who had become addicted to the rarefied atmosphere of the Pandava palace, to leave home without anxiety. “A first-class man wakes up and realizes the falsity and misery of this material world. He thus leaves home and depends fully on the Supreme Personality of Godhead within his heart. Please, therefore, leave for the North immediately without letting your relatives know.”

The time had come for Dhrtarastra to take his stand. Was he going to go on wasting his life, refusing to admit that his position at court was morally untenable? Or was he going to polish up his tarnished values during the last days of his life? The common practice in Vedic civilization was for a man to set aside the last part of his life for the sole purpose of self-realization and the attainment of salvation. Therefore, Vidura’s good advice carried more weight than it would today.

Because Vidura was genuinely compassionate toward Dhrtarastra, his words illuminated the consciousness that had been haunted by darkness for so many years. Dhrtarastra clearly saw the truth in what Vidura was saying, and in an extraordinary display of resoluteness, left the palace without fanfare to set out on his lonely path. Gandhari followed her husband as an expression of her loyalty, although he did not ask her to do so.

They went to a place called Saptasrota, on the southern side of the Himalayan mountains, where the waters of the Ganges divide into seven parts. There Dhrtarastra practiced mystic yoga, bathing three times daily, performing a fire sacrifice, and drinking only water. In this way he was able to control his mind and free it from thoughts of family life. He was able to lock up the Pandora’s box of material desires and throw away the key, and he thus finally freed himself of the desire to play God with the lives of others.

Long before, when he had declined to cooperate with the Supreme Lord Krishna, Dhrtarastra had simply increased the false egotism covering his real spiritual identity. Now, through the yogic process, he learned to concentrate all his senses on the Supreme and to understand himself as the Lord’s eternal servitor. Thus he got free from the material propensities of hankering for power and wealth and attained his spiritual identity by the grace of his brother Vidura. Krishna had shown his mercy upon Dhrtarastra by sending Vidura, and when the old king was actually practicing the instructions of Vidura, the Lord directly helped him to attain the highest perfectional stage.

After some time, Dhrtarastra quit his body by his developed mystic power, and the body burned to ashes. In this way, the king who could not live with honor died with honor. By the mercy of Lord Krishna’s devotee, he was able to make his life a success.

Krishna is kind to everyone, everywhere. So the leaders of today’s society can also benefit from His mercy, as much as the blind king did. The modern Vidura is His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, and the modern yoga process is chanting the names of God. They both stand ready to help our modern Dhrtarastras come to Krishna consciousness—either in retirement, or better yet in youth, to be able to lead others to the transcendental goal.

Leave a Reply