Now that scientists like Jacques Monod have helped us toward “an anxious quest in a frozen universe of solitude,” here are some time-tested secrets for rediscovering the warm and wonderful.

“Alienation,” social scientists say, is our inability to relate meaningfully to others, to nature, and to ourselves. As Dr. Urie Bronfenbrenner reports in Scientific American, alienation is growing at an alarming and unprecedented rate. This trend appears to result from a radically different life view imposed upon the past few generations.

Not so many years ago, most people saw in human events and the things of nature the hand of a purposeful God. But today, many scientists, such as the late Nobel Prize winner Jacques Monod, regard God, meaning, and an intelligence behind the universe as childish concepts. In Monod’s words, man must awaken to

his fundamental isolation. Now does he at last realize that, like a gypsy, he lives on the boundary of an alien world. A world that is deaf to his music, just as indifferent to his hopes as it is to his suffering or his crimes.

God no longer holds “the whole world in His hands.” Now emptiness, the void, accounts for everything, and mankind-long accustomed to living in a world full of meaning—grapples with how to adjust to this revolutionary change.

It hasn’t been easy, nor the results encouraging. As historian Theodore Roszak observes, twentieth century society has projected “a nihilistic imagery unparalleled in human history.” The main themes of the century stand out as disillusionment, pessimism, and the lure of destruction.

Clearly, Monod was no maverick. Nobel laureate Francis Crick (co-unraveller of the DNA code) has said, “I myself, like many scientists, believe that the soul is imaginary.” In schools all over the world, students learn that man is a “naked ape,” or, as one textbook puts it, “nothing but a complex biochemical mechanism powered by a combustion system which energizes computers with prodigious storage facilities for retaining encoded information.”

This main theme in modern science—”reductionism”—has drawn much criticism. Dr. Roszak, for instance, depicts reductionism as “the effort to turn what is alive into a mere thing.” Psychiatrists and social commentators like Dr. Viktor E. Franki feel that the society spawned by reductionism is wearing away humanity’s psychological health. Recently, an international congress of psychoanalysis concluded that “ever more patients are suffering from a lack of life content.”

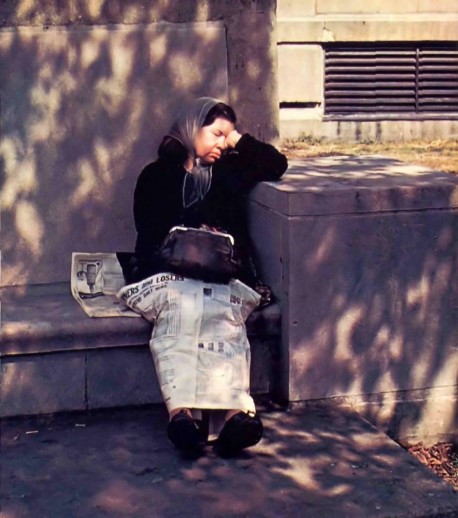

In the layman’s language, “lack of life content” means anxiety, stress, boredom, apathy, despair, meaninglessness, cynicism—in a word, alienation. As playwright Eugene Ionesco writes, “Cut off from religion, metaphysics, and roots, man is lost. His actions become senseless, useless, absurd.”

By defining man as a machine and affording him no more dignity than a stone or a piece of broken glass, reductionism has cut deep. Our sense of wonder, our ability to appreciate life’s everyday beauties—the sun, the moon, the fragrance of the earth—has comes into question and grown dull.

A Return to the Root

The effects of reductionism are prompting many people to reexplore the spiritual dimension. English novelist J.B, Priestly, for one, visited the Colorado River and observed how it had carved out the Grand Canyon. He said, “You feel when you are there that God gave the river its instructions.”

Dr. Roszak asks, “Why, one wonders, should it be thought crude or rudimentary to find divinity brightly present in the world where others find only dead matter or an inferior order of being?”

In their textbook Psychology, Lindzey, Hall, and Thompson confirm, “All human cultures from the dawn of history have valued the mystical or religious experience. Man always seems to be searching for some higher form of consciousness or awareness.” This statement returns us to the crux of the problem: twentieth century man has deviated from this search and is paying the price—alienation.

In the past, people solved alienation by experiencing what we might call “the divine presence,” both within themselves and in the people and things around them. But simply wiping the dust off old catechisms and relearning their formulas by rote won’t help us. The emphasis of numerous religious groups on memorizing doctrines rather than on experiencing God has only weakened people’s convictions—and has helped (or even started) the process of alienation.

Despite its obvious shortcomings, modern science has taught us at least one thing: we should test a truth before we accept it. And thousands of years ago, sages and yogis had the same idea. They advised their students not to dwell in doctrines but to link themselves with the living world around them. By following the sages’ directions for meditating on nature, the students experienced truth for themselves.

Appropriately, the handbook of spiritual education, the Bhagavad-gita, deals extensively with alienation and its cure. At the beginning, Arjuna suffers from intense alienation. “My mind is reeling…. Now I am confused about my duty and have lost all composure because of weakness…. I can find no means to drive away this grief which is drying up my senses.” The Supreme Lord, Sri Krishna, instructs Arjuna on how to rediscover his ability to live in a meaningful. God-conscious way.

About halfway through the work, Arjuna asks, “How should I meditate on You? In what various forms are You to be contemplated, O Blessed Lord?” (Bg. 10.17). In reply, the Lord suggests ways to realize His presence in the happenings of this world. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada comments that since it is difficult to perceive God directly, “One is advised to concentrate the mind on physical things in order to see how Krishna [God] is manifested by physical representations.”

This process is like appreciating an artist through his art. When we see a masterpiece, we naturally admire the talent and skill of its creator. The yogis and sages report that by looking upon the universe with this same sense of wonder, we can experience samadhi (blissful immersion in God consciousness), or what today’s psychologists call a “peak experience.” Alienation vanishes, and we feel reconnected to the root of existence—Krishna.

On the pages that follow, the reader will find some of Lord Krishna’s suggestions, accompanied by short meditations—all in all, “enough to make you wonder.” As Srila Prabhupada has remarked, by reawakening this sense of wonder “one becomes increasingly enlightened, and he enjoys life with a thrill, not only for some time, but at every moment.”

“Of lights I am the radiant sun.”

As scientists have discovered, the sun gives out more energy in one second than all the earth’s people could use in millions of years. Also, the sun is the light of our lives; without it the entire world would be dark. Even our light bulbs are simply reservoirs of the sun’s rays. And, as we learn from the Vedic literature, the sun itself is but a tiny reservoir of the Lord’s glowing effulgence.

“Of purifiers I am the wind.”

Most people have experienced the zestfulness of a breezy day, or, in winter, those gusts that simply “go right through you.” The wind, whooshing all around, seems to wash us even more smoothly and swiftly than water (and it even sounds clean). The wind, then, suggests the all-pervasive, all-purifying Lord.

“Of bodies of water I am the ocean.”

Of all bodies of water, the ocean runs the deepest and stretches the farthest. In fact, for sheer greatness, practically nothing else in the world can compare to it. So the ocean reminds us of the Lord’s greatness.

“I am the original fragrance of the earth.”

Everything in this world has a certain flavor or fragrance, as the fragrance of a pine tree, a lemon, or a rose. This pure, original flavor in everything is Krishna.

“I am the taste of water.”

Most of us have had the experience (say, after driving through a desert) of walking right past the soft drink dispenser to the water fountain. When you’re really thirsty, nothing satisfies like water—the pure taste of water, which is one of the energies of the Lord.

“I am the heat in fire.”

We need fire for our factories, our furnaces, and our frying pans. As we’ve already seen, fire comes from the sun, and the sun comes from Krishna. So the fire and the heat of the fire are Krishna.

“I am the healing herb.”

How could it be that things that grow in the ground provide just the right remedies for worrisome diseases? When man-made “wonder drugs” come about only after much care and concentration, do these natural wonder drugs come about, as scientists say, by chance—or by the Lord’s kindness?

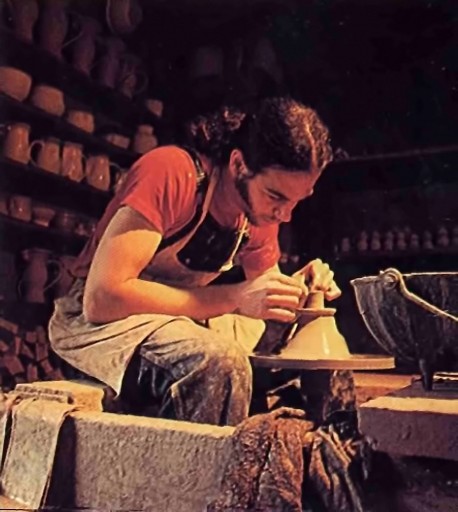

“I am the ability in man.”

How can a master musician or artist do with ease what most of us couldn’t do with the greatest effort? What makes the difference between “all thumbs” and “all-star”? The answer is Krishna.

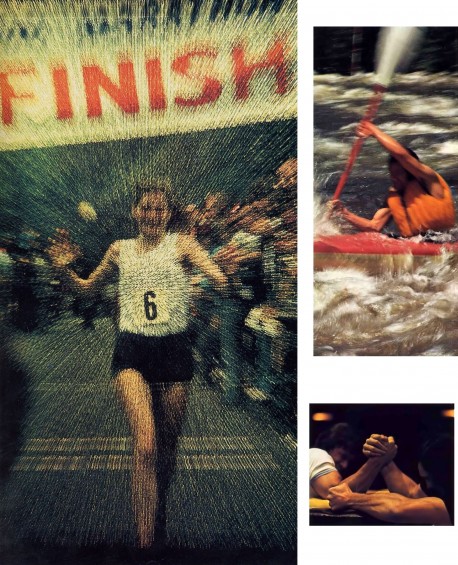

“I am victory, I am adventure, and I am the strength of the strong.”

Conquest and the questing spirit, even the questing capacity—all come from Lord Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

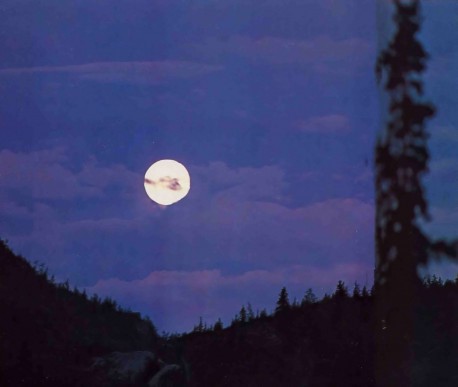

“Among the stars I am the moon.”

When the moon fills the night with its cool light, people feel refreshed. And the moon’s light makes vegetables grow and become succulent. Thus, the moon brings to mind the cooling and soothing face of the Lord.

“Among subduers I am time.”

“The glory that was Rome”-and the glory that was anything else—just couldn’t outlast eternal time, by which Lord Krishna gets the best of everything and everyone.

“Of secret things I am silence.”

Our ability to hold forth on some topic, or to hear about it, or to hush up about it, comes from the Lord.

“Of weapons I am the thunderbolt.”

The thunderbolt, the ultimate shocker, gives us some idea of the Lord’s power.

“Of seasons I am the flower-bearing spring.”

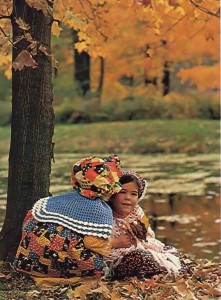

Everyone likes spring. It’s neither too hot nor too cold, the flowers and trees blossom, the grass comes alive, and everything flourishes. The greens and pinks and blues and yellows, the fresh-smelling breezes, the sun-filled evenings—as with any other work of art, these masterstrokes tell us something about the artist. The most joyful of all seasons, spring reminds us of the most joyful of all persons, Krishna.

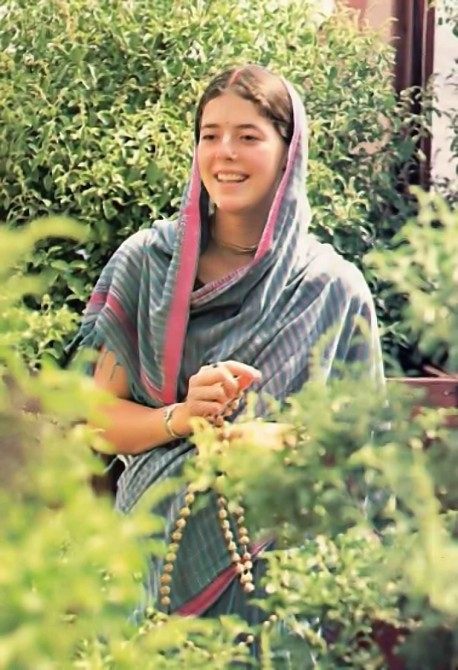

“Of sacrifices I am the chanting of the holy names (japa).”

Everybody is giving his time and energy to get something he can enjoy. The father works hard all day so that he can enjoy the happiness of his wife and children. The politician spends long hours in meetings and masterminding sessions so that he can have a satisfied constituency. Everybody is taking pains to please somebody. Yet there’s a way to please everybody, and it’s pleasing in itself—chanting the Lord’s holy names.

[…] Our Sense of Wonder — Gone Under […]