Time destroys mundane love for a formless “God”

—but not love for the supremely and eternally attractive person.

by Ravindra-Svarupa Dasa

Because my family frequently moved when I was a child, I attended a succession of Sunday schools and vacation Bible schools. Consequently, I had occasion to ask a number of religious instructors a question that had me genuinely puzzled. I knew that God was so great and powerful that it cost Him virtually no effort at all to maintain and control this vast creation. He could do it with the tip of His little finger, so to speak. So, I wanted to know, what did God do with his time? How did He occupy Himself in His heavenly kingdom?

I kept on asking this question because no one could answer it. My teachers would first be startled—as though the question had never occurred to them—and then frankly nonplussed. After a while, of course, I stopped asking. It seemed to me that God must be sitting up there on His throne, just as bored in heaven as I was in Sunday school.

And there was this related question: What did we do in paradise? What made it such a desirable place to be? Here I was offered a variety of answers, but the dominant image of the kingdom of God I retained from childhood is of a sort of perpetual suburban Saturday spent on the back patio in an interminable family reunion with pious resurrected relatives, while Jesus wanders in white robes from house to house through the back yards. I did not find this a particularly attractive prospect for eternity.

In my teens, I encountered a more sophisticated notion of paradise: Our beatitude there arises from our perpetual vision of God. This idea is enshrined at the conclusion of The Divine Comedy. When Dante at last comes directly before God in paradise, he encounters an awesome “Eternal Light” surrounded by nine concentric circles of circumnavigating angels. Dante became “wholly rapt” before this light and could only gaze upon it, “fixed, motionless, and intent.”

This account had its interest for me, but staring at a bright light was nowhere near as alluring as the variety of relationships I was beginning to explore in the world around me. God and His kingdom were simply not attractive enough to compete with the offerings of the material world.

Yet obviously that must be wrong. For God, by definition, is the greatest and best of all. Consequently, He must be the supremely lovable being, the most attractive and alluring of all persons. Similarly, His kingdom must be the most excellent and most desirable of all neighborhoods. It follows, then, that if we really knew what God was like, and really knew what our relationship with Him in His own abode was to be, no other persons and no other relationships would claim our interest.

Just for that reason. God has in fact revealed to the world the intimate and confidential details concerning Himself, His own residence, and the relationships He pursues with His pure devotees there. This supreme revelation of Krsna—God in His highest and most attractive feature—is recorded in the Sanskrit text called Srimad-Bhagavatam.

It is established practice for experts in every field to organize knowledge of their subject into levels of increasing mastery and to compose textbooks for each grade, from the most elementary to the most advanced. So it is for knowledge of God, and the Srimad-Bhagavatam is among the most advanced texts in that science. It begins where the more widely known Bhagavad-gita leaves off.

The Bhagavad-gita establishes that Krsna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead, that there is no truth higher than He, and that all different paths of religion are just a seeking after Him. Therefore, Krsna’s final instruction in the Bhagavad-gita is that one should “abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me” (18.66). The Srimad-Bhagavatam opens with the statement that it is intended for those who have complied with Krsna’s order, and it identifies the “religion” Krsna tells us to abandon as kaitava-dharma—religion contaminated by various sorts of material ambitions. Pure religion, according to the Bhagavatam, is service rendered to God without interruption or selfish motivation, and the Srimad-Bhagavatam itself is specifically intended for those who are serving God in this way. Such pure devotees are the most advanced students in the science of God. It is no wonder, then, that in the text meant for them we find the most complete disclosures of God.

In the Bhagavad-gita (4.11), Krsna states the principle by which He discloses Himself to us. “All of them—as they surrender unto Me—I reward accordingly. Everyone follows my path in all respects.” While all people on the path of religon may be progressing toward God, they are considered more or less advanced according to their degree of surrender to Him. And according to that degree of surrender, God reveals Himself.

For example, let us consider a level of spiritual advancement known as karma-kanda. A person on this platform (called a karmi) is allowed restricted material enjoyment according to the regulations given by God in scripture. The karmi is given to know that if he piously follows these regulations he will earn the reward of future enjoyment and that disobedience will bring him punishment. Thus it is a system of rewards and punishments that impels the karmi to follow God’s orders. Such a person will make some spiritual advancement, because at least he acknowledges the supremacy of God and is restricted in his sense gratification.

Karma-kanda religion, in fact, was precisely the sort of religion I learned in Sunday school. We understood God mostly as the cosmic fulfiller of our needs and desires and as the supreme judge, whose great power over us inspired proper awe, veneration, and fear of disobedience. We envisioned God’s kingdom as a place of uninterrupted (if somewhat dispassionate) material enjoyment, a reward for our good behavior. And we thought of God Himself as a voice issuing from on high, ordering, cajoling, and threatening. He was a benevolent but stern parent, remote but still attentive, toward whom we, His children, should feel both gratitude and fear.

Certainly, one sometimes comes across more advanced understandings in Judeo-Christian traditions, but the form of religion I have just described is by far the most common. And it is this sort of religion—religion contaminated by material desires—that we have to abandon if we are to approach closer to God and ultimately meet Him in His supremely attractive personal form, Krsna.

What Westerners find most startling about the revelation of God as Krsna is that Krsna has a humanlike form. They find it hard to believe that this is an advanced realization of God, since they have been taught that God is formless, featureless spirit, and they take Krsna to be an anthropomorphic fantasy. Furthermore, they see that Krsna disports Himself as a beautiful, youthful cowherd boy surrounded by a simple village community of relatives and friends. Where, then, is the power and majesty that properly belong to God? Where is the controller of the cosmos, the mighty judge of the living and the dead? How can a simple, charming cowherd boy inspire the fear, trembling, and sense of creaturliness that we should feel before God?

To be sure, the first lesson in religion is to appreciate the infinite greatness of God and to realize that we are only His infinitesimally small creatures. Unfortunately, this lesson can be very hard for us to learn, because we have come to this material world in rebellion against God. We do not wish to remain subordinate to God. Those who are the most envious of God deny His existence. There are others who acknowledge God’s greatness, even though the tendency to be independent remains within their hearts. Their lack of complete surrender to God is shown by their engagement in materially motivated religion, and God reveals Himself to those in this early stage of spiritual advancement only in His might and majesty. Although they may know theoretically that God is a person. God keeps His personal features hidden from them. He remains aloof, inscrutable, inaccessible. In this way, God exacts the proper respect and veneration from those who still have the inclination to disobey Him.

But it is also part of God’s greatness that He enters into more intimate and familiar relationships with those devotees who have become completely pure in heart and who serve Him solely out of love, without any expectation of return. To them He reveals His supreme personal form. Because this form resembles ours, the ignorant will call it anthropomorphic. But the truth is that our human body is theomorphic. We are made in the image of God. Of course, our copy of God’s body is a temporary, material replica, while God’s own body is spiritual and eternal. Speculators may think that a body, as such, is a bad thing and thus deny that God has form, but only a material form that grows old, becomes diseased, and dies should be rejected. The eternal, ever-youthful body of Krsna is not subject to those conditions. To reject God’s form on the grounds that if God had a body it would be a material body like ours is to be guilty of anthropomorphism.

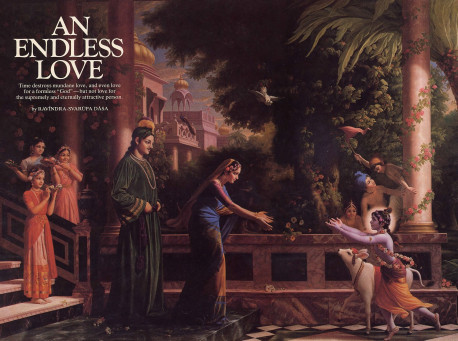

Krsna is reluctant to reveal Himself to everyone. For Krsna sets aside all lordliness and signs of dominion, allows His beauty to completely overpower His majesty, and simply engages in developing pastimes of love with His devotees. To facilitate intimate relationships, Krsna causes His devotees to forget that the beautiful, exquisitely charming object of their love is God. And so He dwells in His eternal abode, playing as a simple village cowherd boy, ever increasing the unending bliss of His devotees.

Pure devotees most appreciate God in this confidential, all-attractive feature, but others, seeing Krsna in His human form, react differently. Krsna mentions this in the Bhagavad-gita (9.11): “Fools deride Me when I descend in the human form. They do not know My transcendental nature and My supreme dominion over all that be.” Out of envy, they will claim either that Krsna is an ordinary human being or that ordinary human beings are God.

In spite of this danger, Krsna Himself descended onto this planet five thousand years ago, bringing with Him His eternal associates, and for a time displayed His most confidential and intimate pastimes at the tract of land known as Gokula Vrndavana. More than anything else, God wants the fallen souls suffering in the material world to come back to Him, and therefore He decided to show the unparalleled sweetness of the limitlessly variegated loving relationships that He and His devotees enjoy without end in His supreme abode. The world already knew God as all-mighty and all-seeing; now it would know Him as all-attractive.

Learned devotees have carefully studied these pastimes of Krsna as they are recorded in the Srimad-Bhagavatam and other texts, and they have discovered five principal kinds of relationships devotees have with God. Each of these relationships has a particular taste that the devotee relishes. In Sanskrit that taste is called rasa. The five principal rasas, listed in order of increasing intimacy, are neutrality, or passive adoration, servitorship, fraternal love, parental love, and conjugal love.

In the rasa of neutrality the devotee is so overwhelmingly conscious of God’s greatness that He can only adore Him passively. The devotee feels no impetus to render service, because he thinks that God is so great that there is nothing he can do for Him. Dante’s description of the Beatific Vision as producing stunned, enraptured awe before God suggests that neutrality is his highest conception of a relationship with God. In the rasa of servitorship there are also feelings of subordination, but they are not so extreme as to prevent the devotee from actively serving his Lord. In the fraternal rasa the devotee associates with Krsna on an equal level, as a friend of the same age and sex. And in the parental rasa Krsna enjoys having His devotee act as His superior. Krsna becomes the child, and His devotee loves and serves Him in the position of His mother or father. Finally, the most intimate rasa is conjugal love; here, the devotee regards Krsna as husband or lover.

Just as Krsna’s body is the prototype of our material body, so Krsna’s transcendental relationships are the prototypes of material relationships, which are perverted reflections of the originals. Accordingly, we should not project the quality of material affairs onto the spiritual rasas. The sublime exchange of ecstatic emotions in spiritual bodies that takes place between Krsna and the cowherd girls of Vrndavana cannot be compared with the gross features of material sex. Moreover, the relationships with Krsna in the spiritual world never grow stale or come to an end like the relationships in this world. In the spiritual world, all rasas continue for eternity.

Here in the material world we find reflections of these relationships, and because we are always interested in tasting rasas, we constantly enter into them and try to perpetuate them. Our problem, however, is that we do not find the satisfaction we seek. We are inevitably disappointed. For all rasas in the material world are eclipsed. Here everything is changing, unstable, and temporary. We form relationships with our heroes, our friends, our children, and our lovers or spouses, and we start off with vast hope and great expectations. We all remember—ruefully—that intoxicating promise of endless love our first adolescent infatuation brought. And what can match the boundless hope a mother feels when she first holds her newborn? Yet none of these relationships deliver what they promise. As we grow older, we become “mature” by learning how to live with dead rasas, failed relationships, broken hearts. And, having discovered that my hero has feet of clay, or that my best friend has betrayed my trust, or having seen what was once the sweetest girl of my dreams stare at me over a lawyer’s table with murderous hate, or having stood over the small grave of my child, I will find it hard, or even impossible, to love as I once hoped I could.

Our propensity to love tends naturally to expand without limit, yet in this world it meets with repeated impediments. The baffling of our urge to love becomes one of the most tragic features of life. The crux of the problem is that although we want to love. we are never more vulnerable than when we do. As soon as we love someone, we open ourselves to rejection, betrayal, separation, loss, and all the attending anguish and pain. Experience of these things has filled the world with bitter and disappointed people, cynics and misanthropes.

But even before we have suffered the pains of thwarted love, we aren’t able to love fully and unconditionally. There is an essential incompatability between what we are and what we can love in this world, and in our hearts we know it. Our desire to love without limit and without end is a clear indication that we are ourselves eternal, spiritual beings. At the same time, whatever we can love in this world is temporary and material. Consequently, we cannot love without fear, and, consciously or unconsciously, from the outset we cannot help but withhold the full investment of our love.

A frequent theme in literature concerns a hero or heroine who loves recklessly and without restraint, inevitably undergoes the most intense sort of suffering, and finally meets with a tragic or pitiful death. We may take these stories as cautionary tales. Yet we really don’t need them to remind us of the constant frustration of our being. There is no adequate object for our love in this world.

Therefore, out of boundless compassion for us. Krsna reveals His kingdom of transcendental, unrestricted love, in which He is eternally manifest as the ultimate object of affection—the most perfect hero, master, friend, child, and lover. His beauty is unrivaled, and His personality, expressed in infinitely varied exchanges of love, is ceaselessly fascinating. When we turn to Krsna, our loving propensity breaks loose at last from the tight confines of matter and opens up into an ever-expanding flow that never meets any resistance. That is why Krsna is perpetually inviting us to come to Him in His eternal abode and enjoy with Him forever the delights of an endless love.

Leave a Reply