Chanting and Speaking for All to Hear

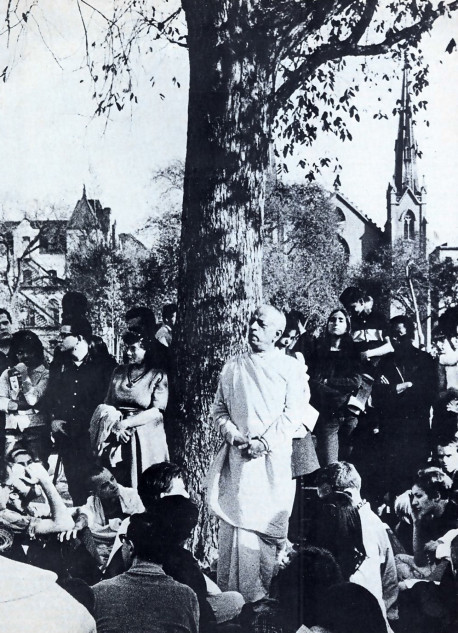

Fall, 1966: Tompkins Square Park, the Lower East Side, New York. Street sadhus and street musicians, hippie seekers and the simply curious—all joined with Srila Prabhupada in chanting Hare Krsna in the park.

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

Since he had broken the American silence with his public chanting of Hare Krsna in Washington Square Park, in the heart of Greenwich Village, Srila Prabhupada had been sending out small “parades” of devotees, chanting and playing hand cymbals through the streets of the Lower East Side. Now he was ready for a bold foray into one of the centers of the midsixties hippie scene—Tompkins Square Park.

Tompkins Square Park was the park on the Lower East Side. Since the Weather was still warm and it was Sunday, the park was crowded with people. Almost all the space on the benches that lined the walkways was occupied. There were old people, mostly Ukrainians, dressed in outdated suits and sweaters, even in the warm weather, sitting together in clans, talking. There were many children in the park also, mostly Puerto Ricans and blacks but also fair-haired, hard-faced slum kids racing around on bikes or playing with balls and Frisbees. The basketball and handball courts were mostly taken by the teenagers. And as always, there were plenty of loose, running dogs.

And the hippies were there, different from the others. The bearded Bohemian men and their long-haired young girlfriends dressed in old blue jeans were still an unusual sight. Even in the Lower East side melting pot, their presence created tension. They were from middle-class families, and so they had not been driven to the slums by dire economic necessity. This created conflicts in their dealings with the underprivileged immigrants. And the hippies’ well-known proclivity for psychedelic drugs, their revolt against their families and affluence, and their absorption in the avant-garde sometimes made them the jeered minority among their neighbors. But the hippies just wanted to do their own thing and create their own revolution for “love and peace,” so usually they were tolerated, although not appreciated.

There were various groups among the young and hip at Tompkins Square Park. There were friends who had gone to the same school together, who took the same drug together, or who agreed on a particular philosophy of art, literature, politics, or metaphysics. There were lovers. There were groups hanging out together for reasons undecipherable, except for the common purpose of doing their own thing. And there were others, who lived like hermits—a loner would sit on a park bench, analyzing the effects of cocaine, looking up at the strangely rustling green leaves of the trees and the blue sky above the tenements and then down to the garbage at his feet, as he helplessly followed his mind from fear to illumination, to disgust to hallucination, on and on, until after a few hours the drug began to wear off and he was again a common stranger. Sometimes they would sit up all night, “spaced out” in the park, until at last, in the light of morning, they would stretch out on benches to sleep.

But whatever the hippies’ diverse interests and drives, the Lower East Side was an essential part of the mystique. It was not just a dirty slum; it was the best place in the world to conduct the experiment in consciousness. For all its filth and threat of violence and the confined life of its brownstone tenements, the Lower East Side was still the forefront of the revolution in mind expansion. Unless you were living there and taking psychedelics or marijuana, or at least intellectually pursuing the quest for free personal religion, you weren’t enlightened, and you weren’t taking part in the most progressive evolution of human consciousness. And it was this searching—a quest beyond the humdrum existence of the ordinary, materialistic, “straight” American—that brought unity to the otherwise eclectic gathering of hippies on the Lower East Side.

Swamiji, accompanied by half a dozen disciples, was walking the eight blocks to the park from the storefront. Brahmananda carried the harmonium and the Swami’s drum. Kirtanananda, now shaven-headed at Swamiji’s request and dressed in loose-flowing canary yellow robes, created an extra sensation. Drivers pulled their cars over to have a look, their passengers leaning forward, agape at the outrageous dress and shaved head. As the group passed a store, people inside would poke each other and indicate the spectacle. People came to the windows of their tenements, taking in the Swami and his group as if a parade were passing. The Puerto Rican tough guys, especially, couldn’t restrain themselves from exaggerated reactions. “Hey, Buddha!” they taunted. “Hey, you forgot to change your pajamas!” They made shrill screams as if imitating Indian war whoops they had heard in Hollywood westerns.

“Hey, A-rabs!” exclaimed one heckler, who began imitating what he thought was an Eastern dance. No one on the street knew anything about Krsna consciousness, nor even of Hindu culture and customs. To them, the Swami’s entourage was just a bunch of crazy hippies showing off. But they didn’t quite know what to make of the Swami. He was different. Nevertheless, they were suspicious. Some, however, like Irving Halpern, a veteran Lower East Side resident, felt sympathetic toward this stranger, who was “apparently a very dignified person on a peaceful mission.”

Irving Halpern: A lot of people had spectacularized notions of what a swami was. As though they were going to suddenly see people lying on little mattresses made out of nails-and all kinds of other absurd notions. Yet here come just a very graceful, peaceful, gentle, obviously well-meaning being into a lot of hostility.

“Hippies!”

“What are they, Communists?”

While the young taunted, the middle-aged and elderly shook their heads or stared, cold and uncomprehending. The way to the park was spotted with blasphemies, ribald jokes, and tension, but no violence. After the successful kirtana in Washington Square Park, Prabhupada had regularly been sending out “parades” of three or four devotees, chanting Hare Krsna and playing hand cymbals through the streets and sidewalks of the Lower East Side. On one occasion, they had been bombarded with water balloons and eggs, and they were sometimes faced with bullies looking for a fight. But they were never attacked—just stared at, laughed at, or shouted after.

Today, the ethnic neighbors just assumed that Prabhupada and his followers had come onto the streets dressed in outlandish costumes as a joke, just to turn everything topsy-turvy and cause stares and howls. They felt that their responses were only natural for any normal, respectable American slum-dweller.

So it was quite an adventure before the group even reached the park. Swamiji, however, remained unaffected. “What are they saying?” he asked once or twice, and Brahmananda explained. Prabhupada had a way of holding his head high, his chin up, as he walked forward. It made him look aristocratic and determined. His vision was spiritual—he saw everyone as a spiritual soul and Krsna as the controller of everything. Yet aside from that, even from a worldly point of view he was unafraid of the city’s pandemonium. After all, he was an experienced “Calcutta man.”

The kirtana had been going for about ten minutes when Swamiji arrived. Stepping out of his white rubber slippers, just as if he were home in the temple, he sat down on the rug with his followers, who had now stopped their singing and were watching him. He wore a pink sweater, and around his shoulders a khadi wrapper. He smiled. Looking at his group, he indicated the rhythm by counting, one . . . two . . . three. Then he began clapping his hands heavily as he continued counting, “One . . . two . . . three.” The karatalas followed, at first with wrong beats, but he kept the rhythm by clapping his hands, and then they got it, clapping hands, clashing cymbals artlessly to a slow, steady beat.

He began singing prayers that no one else knew. Vande ‘ham sri-guroh sri-yuta-pada-kamalam sri-gurun vaisnavams ca. His voice was sweet like the harmonium, rich in the nuances of Bengali melody. Sitting on the rug under a large oak tree, he sang the mysterious Sanskrit prayers. None of his followers knew any mantra but Hare Krsna, but they knew Swamiji. And they kept the rhythm, listening closely to him while the trucks rumbled on the street and the conga drums pulsed in the distance.

As he sang—sri-rupam sagrajatam—the dogs came by, kids stared, a few mockers pointed fingers: “Hey, who is that priest, man?” But his voice was a shelter beyond the clashing dualities. His boys went on ringing cymbals while he sang alone: sri-radha-krsna-padan.

Prabhupada sang prayers in praise of the pure conjugal love of Srimati Radharani for Krsna, the beloved of the gopis. Each word, passed down for hundreds of years by the intimate associates of Krsna, was saturated with deep transcendental meaning that only he understood. Saha-gana-lalita-sri-visakhanvitams ca. They waited for him to begin Hare Krsna, although hearing him chant was exciting enough.

More people came—which was what Prabhupada wanted. He wanted them chanting and dancing with him, and now his followers wanted that too. They wanted to be with him. They had tried together at the U.N., Ananda Ashram, and Washington Square Park. It seemed that this would be the thing they would always do—go with Swamiji and sit and chant. He would always be with them, chanting.

Then he began the mantra-Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. They responded, too low and muddled at first, but he returned it to them again, singing it right and triumphant. Again they responded, gaining heart, ringing karatalas and clapping hands one . . . two . . . three, one . . . two . . . three. Again he sang it alone, and they stayed, hanging closely on each word, clapping, beating cymbals, and watching him looking back at them from his inner concentration—his old-age wisdom, his bhakti—and out of love for Swamiji, they broke loose from their surroundings and joined him as a chanting congregation. Swamiji played his small drum, holding its strap in his left hand, bracing the drum against his body, and with his right hand playing intricate mrdanga rhythms.

Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. He was going strong after half an hour, repeating the mantra, carrying them with him as interested onlookers gathered in greater numbers. A few hippies sat down on the edge of the rug, copying the cross-legged sitting posture, listening, clapping, trying the chanting, and the small inner circle of Prabhupada and his followers grew, as gradually more people joined.

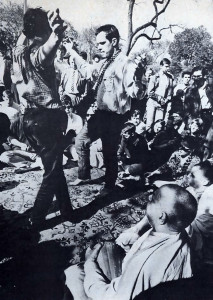

As always, his kirtana attracted musicians.

Irving Halpern: I make flutes, and I play musical instruments. There are all kinds of different instruments that I make. When the Swami came, I went up and started playing, and he welcomed me. Whenever a new musician would join and play their first note, he would extend his arms. It would be as though he had stepped up to the podium and was going to lead the New York Philharmonic. I mean, there was this gesture that every musician knows. You just know when someone else wants you to play with them and feels good that you are playing with them. And this very basic kind of musician communication was there with him, and I related to it very quickly. And I was happy about it.

Lone musicians were always loitering in different parts of the park, and when they heard they could play with the Swami’s chanting and that they were welcome, then they began to come by, one by one. A saxophone player came just because there was such a strong rhythm section to play with. Others, like Irving Halpern, saw it as something spiritual, with good vibrations. As the musicians joined, more passersby were drawn into the kirtana. Prabhupada had been singing both lead and chorus, and many who had joined now sang the lead part also, so that there was a constant chorus of chanting. During the afternoon, the crowd grew to more than a hundred, with a dozen musicians trying—with their conga and bongo drums, bamboo flutes, metal flutes, mouth organs, wood and metal “clackers,” tambourines, and guitars—to stay with the Swami.

Irving Halpern: The park resounded. The musicians were very careful in listening to the mantras. When the Swami sang Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama Rama Rama, Hare Hare, there was sometimes a Krsna, a tripling of what had been a double syllable. It would be usually on the first stanza, and the musicians really picked up on it. The Swami would pronounce it in a particular way, and the musicians were really meticulous and listened very carefully to the way the Swami would sing. And we began to notice that there were different melodies for the same brief sentence, and we got to count on that one regularity, like one would count on the conductor of an orchestra or the lead singer of a madrigal. It was really pleasant, and people would dig one another in their ribs. They would say, “Hey, see!” We would catch and repeat a particular subtle pronunciation of a Sanskrit phrase that the audience, in their enthusiasm, while they would be dancing or playing, had perhaps missed. Or the Swami would add an extra beat, but it meant something, in the way in which the drummer, who at that time was the Swami, the main drummer, would hit the drums.

I have talked to a couple of musicians about it, and we agreed that in his head this Swami must have had hundreds and hundreds of melodies that had been brought back from the real learning from the other side of the world. So many people came there just to tune in to the musical gift, the transmission of the dharma. “Hey,” they would say, “listen to this holy monk.” People were really sure there were going to be unusual feats, grandstanding, flashy levitation, or whatever else people expected was going to happen. But when the simplicity of what the Swami was really saying, when you began to sense it—whether you were motivated to actually make a lifetime commitment and go this way of life, or whether you merely wanted to appreciate it and place it in a place and give certain due respect to it—it turned you around.

And that was interesting, too, the different ways in which people regarded the kirtana. Some people thought it was a prelude. Some people thought it was a main event. Some people liked the music. Some people liked the poetic sound of it.

Then Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky arrived, along with some of their friends. Allen surveyed the scene and found a seat among the chanters. With his black beard, his eyeglasses, his bald spot surrounded by long, black ringlets of hair, Allen Ginsberg, the poet-patriarch come to join the chanting, greatly enhanced the local prestige of the kirtana. Prabhupada, while continuing his ecstatic chanting and drum-playing, acknowledged Allen and smiled.

A reporter from The New York Times dropped by and asked Allen for an interview, but he refused: “A man should not be disturbed while worshiping.” The Times would have to wait.

Allen: Tompkins Square Park was a hotbed of spiritual conflict in those days, so it was absolutely great. All of a sudden, in the midst of all the talk and drugs and theories, for some people to put their bodies, their singing, to break through the intellectual ice and come out with total bhakti that was really amazing.

Prabhupada was striking to see. His brow was furrowed in the effort of singing loud, and his visage was strong. The veins in his temples stood out visibly, and his jaw jutted forward as he sang his “Hare Krsna Hare Krsna” for all to hear. Although his demeanor was pleasant, his chanting was intensive, sometimes straining, and everything about him was concentration.

It wasn’t someone else’s yoga retreat or silent peace vigil, but a pure chanting be-in of Prabhupada’s own doing. It was a new wave, something everyone could take part in. The community seemed to be accepting it. It became so popular that the ice cream vendor came over to make sales. Beside Prabhupada a group of young, blond-haired boys, five or six years old, were just sitting around. A young Polish boy stood staring. Someone began burning frankincense on a glowing coal in a metal strainer, and the sweet fumes billowed among the flutists, drummers, and chanters.

Swamiji motioned to his disciples, and they got up and began dancing. Prabhupada gave a gesture of acceptance by a typically Indian movement of his head, and then he raised his arms, inviting more dancers.

The harmonium played a constant drone, and a boy wearing a military fatigue jacket improvised atonal creations on a wooden recorder. Yet the total sound of the instruments blended, and Swamiji’s voice emerged above the mulling tones of each chord. And so it went for hours. Prabhupada held his head and shoulders erect, although at the end of each line of the mantra he would sometimes shrug his shoulders before he started the next line. His disciples stayed close by him, sitting on the same rug, religious ecstasy visible in their eyes. Finally, he stopped.

Immediately he stood up, and they knew he was going to speak. It was four o’clock, and the warm autumn sun was still shining on the park. The atmosphere was peaceful and the audience attentive and mellow from the concentration on the mantra. He began to speak to them, thanking everyone for joining in the kirtana. The chanting of Hare Krsna, he said, had been introduced five hundred years ago in West Bengal by Caitanya Mahaprabhu. Hare means “O energy of the Lord,” Krsna is the Lord, and Rama is also a name of the Supreme Lord, meaning “the highest pleasure.” His disciples sat at his feet, listening. Raya Rama squinted through his shielding hand into the sun to see Swamiji, and Kirtanananda’s head was cocked to one side, like a bird’s who is listening to the ground.

He stood erect by the stout oak, his hands folded loosely before him in a proper speaker’s posture, his light saffron robes covering him gracefully. The tree behind him seemed perfectly placed, and the sunshine dappled leafy shadows against the thick trunk. Behind him, through the grove of trees, was the steeple of St. Brigid’s. On his right was a dumpy, middle-aged woman wearing a dress and hairdo that had been out of style in the United States for twenty-five years. On his left was a bold-looking hippie girl in tight denims and beside her a young black man in a black sweater, his arms folded across his chest. Next was a young father holding an infant, then a bearded young street sadhu, his long hair parted in the middle, and two ordinary, short-haired middle-class men and their young female companions. Many in the crowd, although standing close by, became distracted, looking off here and there.

Prabhupada explained that there are three platforms-sensual, mental, and intellectual—and above them is the spiritual platform. The chanting of Hare Krsna is on the spiritual platform, and it is the best process for reviving our eternal, blissful consciousness. He invited everyone to attend the meetings at 26 Second Avenue and concluded his brief speech by saying, “Thank you very much. Please chant with us.” Then he sat down, took the drum and began the kirtana again.

If it were risky for a seventy-one-year-old man to thump a drum and shout so loud, then he would take that risk for Krsna. It was too good to stop. He had come far from Vrndavana, survived the non-Krsna yoga society, waited all winter in obscurity. America had waited hundreds of years with no Krsna-chanting. No “Hare Krsna” had come from Thoreau’s or Emerson’s appreciations, though they had pored over English translations of the Gita and Puranas. And no kirtana had come from Vivekananda’s famous speech on behalf of Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. So now that he finally had krsna-bhakti going, flowing like the Ganges to the sea, it could not stop. In his heart he felt the infinite will of Lord Caitanya to deliver the fallen souls.

He knew this was the desire of Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu and his own spiritual master, even though caste-conscious brahmanas in India would disapprove of his associating with such untouchables as these drug-mad American meat-eaters and their girlfriends. But Swamiji explained that he was in full accord with the scriptures. The Bhagavatam had clearly stated that Krsna consciousness should be delivered to all races. Everyone was a spiritual soul, and regardless of birth they could be brought to the highest spiritual platform by chanting the holy name. Never mind whatever sinful things they were doing, these people were perfect candidates for Krsna consciousness. Tompkins Square Park was Krsna’s plan; it was also part of the earth, and these people were members of the human race. And the chanting of Hare Krsna was the dharma of the age.

* * *

Walking back home in the early evening, past the shops and crowded tenements, followed by more than a dozen interested new people from the park, the Swami again sustained occasional shouts and taunts. But those who followed him from the park were still feeling the aura of an ecstasy that easily tolerated a few taunts from the street. Prabhupada, especially, was undisturbed. As he walked with his head high, not speaking, he was gravely absorbed in his thoughts. And yet his eyes actively noticed people and places and exchanged glances with those whom he passed on his way along Seventh Street, past the churches and funeral homes, across First Avenue to the noisy, heavily trafficked Second Avenue, then down Second past liquor stores, coin laundries, delicatessens, past the Iglesia Alianza Cristiana Missionera, the Koh-I-Noor Intercontinental Restaurant Palace, then past the Church of the Nativity, and finally back home to number twenty-six.

A few days later, Ravindra Svarupa was walking down Second Avenue, on his way to the Swami’s morning class, when an acquaintance came out of the Gems Spa Candy and News Store and said, “Hey, your Swami is in the newspaper. Did you see?” “Yeah,” Ravindra Svarupa replied, “The New York Times.”

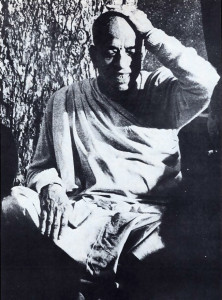

“No,” his friend said. “Today.” And he held up a copy of the latest edition of The East Village Other. The front page was filled with a two-color photo of the Swami, his hands folded decorously at his waist, standing in yellow robes in front of the big tree in Tompkins Square Park. He was speaking to a small crowd that had gathered around, and his disciples were at his feet. The big steeple of St. Brigid’s formed a silhouette behind him.

Above the photo was the single headline, “SAVE EARTH NOW!!” and beneath was the mantra: “HARE KRISHNA HARE KRISHNA KRISHNA KRISHNA HARE HARE HARE RAMA HARE RAMA RAMA RAMA HARE HARE.” Below the mantra were the words, “See Centerfold.” That was the whole front page.

Ravindra Svarupa took the newspaper and opened to the center, where he found a long article and a large photo of Swamiji with his left hand on his head, grinning blissfully in an unusual, casual moment. His friend gave him the paper, and Ravindra Svarupa hurried to Swamiji. When he reached the storefront, several boys went along with him to show Swamiji the paper. “Look!” Ravindra Svarupa handed it over. “This is the biggest local newspaper! Everybody reads it.” Swamiji opened his eyes wide. He read aloud, “Save earth now.” Was it an ecological pun? Was it a reference to staving off nuclear disaster? Was it poking fun at Swamiji’s evangelism?

“Well,” said Umapati, “after all, this is The East Village Other. It could mean anything.”

“Swamiji is saving the earth,” Kirtanananda said.

“We are trying to,” Prabhupada replied, “by Krsna’s grace.” Methodically, he put on the eyeglasses he usually reserved for reading the Bhagavatam and carefully appraised the page from top to bottom. The newspaper looked incongruous in his hands. Then he began turning the pages. He stopped at the centerfold and looked at the picture of himself and laughed, then paused, studying the article. “So,” he said, “read it.” He handed the paper to Hayagriva.

“Once upon a time, . . .” Hayagriva began loudly. It was a fanciful story of a group of theologians who had killed an old man in a church and of the subsequent press report that God was now dead. But, the story went on, some people didn’t believe it. They had dug up the body and found it to be “not the body” of God, but that of His P.R. man: organized religion. At once the good tidings swept across the wide world. GOD LIVES! . . . But where was God?” Hayagriva read dramatically to an enthralled group. . . .

A full-page ad in The New York Times, offering a reward for information leading to the discovery of the whereabouts of God, and signed by Martin Luther King and Ronald Reagan, brought no response. People began to worry and wonder again. “God,” said some people, “lives in a sugar cube.” Others whispered that the sacred secret was in a cigarette.

But while all this was going on, an old man, one year past his allotted three score and ten, wandered into New York’s East Village and set about to prove to the world that he knew where God could be found. In only three months, the man, Swami A.C. Bhaktivedanta, succeeded in convincing the world’s toughest audience—Bohemians, acid heads, potheads, and hippies—that he knew the way to God: Turn Off, Sing Out, and Fall In. This new brand of holy man, with all due deference to Dr. Leary, has come forth with a brand of “Consciousness Expansion” that’s sweeter than acid, cheaper than pot, and nonbustible by fuzz. How is all this possible? “Through Krishna,” the Swami says.

The boys broke into cheers and applause. Acyutananda apologized to Swamiji for the language of the article: “It’s the hippie newspaper.”

“That’s all right,” said Prabhupada. “He has written it in his own way. But he has said that we are giving God. They are saying that God is dead. But it is false. We are directly presenting, ‘Here is God,’ Who can deny it? So many theologians and people may say there is no God, but the Vaisnava hands God over to you freely, as a commodity: ‘Here is God.’ So he has marked this. It is very good.”

The article was long. “For the cynical New Yorker,” it said, “living, visible, tangible proof can be found at 26 Second Avenue, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday between seven and nine.” The article described the evening kirtanas, quoted from Prabhupada’s lecture, and mentioned “a rhythmic, hypnotic sixteen-word chant, Hare Krishna Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare, sung for hours on end to the accompaniment of hand clapping, cymbals, and bells.” Swamiji said that simply because the mantra was there, the article was perfect.

The article also included testimony from the Swami’s disciples:

I started chanting to myself, like the Swami said, as I walked down the street—Hare Krishna Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare—over and over, and suddenly everything started looking so beautiful, the kids, the old men and women . . . even the creeps looked beautiful . . . to say nothing of the trees and flowers. It was like I had taken a dozen doses of LSD. But I knew there was a difference. There’s no coming down from this. I can always do this any time, anywhere. It is always with you.

Without sarcasm, the article referred to the Swami’s discipline forbidding coffee, tea, meat, eggs, and cigarettes, “to say nothing of marijuana, LSD, alcohol, and illicit sex.” Obviously the author admired Swamiji: “the energetic old man, a leading exponent of the philosophy of Personalism, which holds that the one God is a person but that His form is spiritual.” The article ended with a hint that Tompkins Square Park would see similar spiritual happenings each weekend: “There in the shadow of Hoving’s Hill, God lives in a trancelike dance and chant.”

(To be continued)

From Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, by Satsvarupa dasa Gosvami. © 1980 by the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Brought tears to my eyes.